Buddhism has one of the fastest growing communities/fellowship in the world. Many Westerners are impressed by an always-smiling Dalai Lama and his message of happiness. He is the most recognized public figure in the world. But this very successful campaign lets people in the West often forget that the reality faced by millions of Tibetans is anything but freedom and happiness.

Documenting the Struggle of the New Young King of Tibet and His Generation

by David Kaminski

It is a story that has been unfolding for almost 1400 years: the evolution of the Tibetan language into its written form, the reign of kings that began with Songtsen Gampo, the first Dharma King of Tibet in 617 AD, and which continues now into our time with the sole descendant, the young exiled king of Tibet, Namgyal Wangchuk Trichen Lhagyari.

Filmmaker Dirk Simon’s new feature film with the working title The Will to Survive, begun in 2004, uses this historical backdrop to explore the struggle of the new young King of Tibet and his generation who are trying to reflect on their history while they redefine their identities in this new world of shifting politics and changing religious devotion.

Part I:

A Filmmaker’s Notes on Production and Post-Production

Dirk Simon with David Kaminski

The Idea for the Film

The film was originally to tell the story of perhaps the oldest royal lineage alive, the lineage of the Great Religious Kings of Tibet. Considering the last 60 years of Tibetan history, it was fascinating and intriguing to think of a film that features a King whose ancestors not only determined the fate of Tibet over many centuries but who are also credited with bringing Buddhism to the Tibetan people more than a thousand years ago. This lineage and family has been involved in the creation of a religion, Tibetan Buddhism, which today inspires and guides millions of people around the world.

Camera Format… The Beginning

Because of the nature of the project, that is, filming and researching over a long period of time without substantial funding, we ended up using various cameras and formats over the last five years. That was not by choice. We used what we could afford. No matter what camera we used, from the very beginning we shot in 16:9. Besides resolution, the aspect ratio is something very hard to fix later. Sometimes the cameras belonged to friends in Germany, and I ended up shooting in PAL. As a filmmaker, you usually want to avoid this as a format mix always complicates your post production process.

Therefore it was important to secure at least the funding for the principal photography by the end of 2007. I wanted to make sure that we shot with the desired quality and the format. It had to be video, though, as I saw no option to go with film. Considering the circumstances it did not seem practicable or financially realistic.

Cameras and a Strategy

We used two of the new SONY EX1 cameras for most of our work. They offer more or less full HD resolution but are very compact at the same time. Size was an important criterion since we were traveling tens of thousands of miles with the equipment and spending weeks on Indian roads.

There were a few shoots in which we used a SONY F900, a full-size HD camera. The helicopter shots in San Francisco and India, our studio shoot in Delhi, and the filming on two mountaintops in Northern India with several hundred Tibetan students and Tibetan dancers from the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts were all filmed with the F900. It was not only the resolution, considering that we had a lot of distant landscape that was important in most of those scenes. We also used remote heads on both the helicopter as well as on the cranes we shot with. That was another reason to go with the F900 on those days.

Sound, the Third Column

Besides the quality of the images, the quality of the sound was very important. Additional to the photography and the editing, sound is the third column of your film and extremely important. Especially young and independent filmmakers often underestimate the importance and power of the sound quality. In 2008, we recorded most of the time with the Sound Devices 744T Digital Recorder. With the capacity of four channels, a sample rate of 96 kHz and the capability of recording 24-bit audio files, it was the perfect gear. Whenever we could, we recorded surround sound by using two pairs of Audio Technica AT825 stereo microphones.

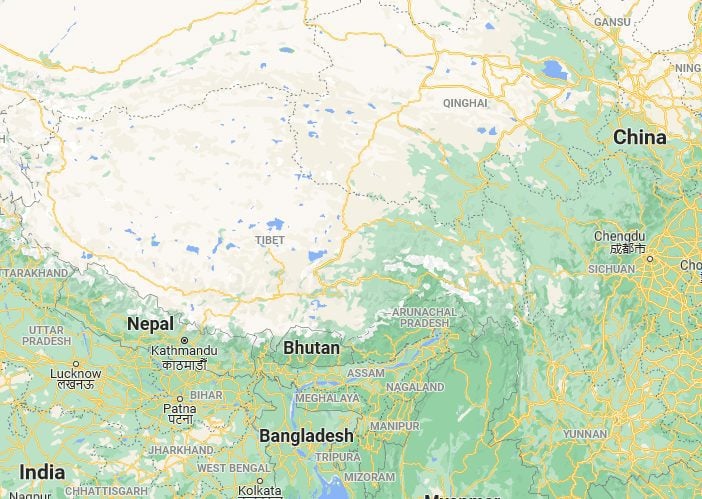

Safety and Secrecy

For a documentary like ours you have to compromise every so often or even sacrifice quality for safety or other reasons. As an example, on our trip to China, we did not take the digital sound recorder or the AT825 stereo microphones. I was too concerned, knowing that security would be extremely tight, and given the circumstances and topic of our film, that the Chinese authorities would identify us as a professional crew no matter what we said. To hire a Chinese sound recordist and equipment for interviews seemed risky because of the nature of the project. Instead, we used Sennheiser shotgun microphones and wireless technology, recording directly onto our cameras.

In addition, a SONY V1U and a SONY HDR-SR12 were used for backup, behind the scenes, and sometimes filming secretly. Especially useful was the HDR-SR 12, which proved to be the perfect mix of quality and handling in the situations where we had to hide the camera. Also, with the plan of being in Beijing for the Olympic Games without press accreditation made it important that we could blend in with the “rich tourist” or “university student”. A lot of the film was shot “guerrilla style”.

I wish we would have had more time in Tibet. But considering the circumstances, I am happy that we were able to go at all. I wish we could interview Tibetans in Tibet. But usually it is too dangerous for them to go on record and I as the filmmaker have a responsibility. I have to be sure that they are safe.

Solving Problems with Mixed Formats

Both main crews were filming with the same type of camera, the SONY EX1. So, there was in general no conflict. However, both cinematographers constantly communicated color temperature, exposure, or other settings to make sure that the footage matches.

When the Olympic torch came to San Francisco, April 17, 2008, we knew it will be a crazy day and we used an additional crew with a Panasonic P2. The P2 crew in San Francisco had to film with the highest available resolution, even if that meant that they would go much faster through their cards and had to back up footage more often. Although the quality is not comparable with the SONY EX1, it still provides a decent resolution for a camera with that size and it was our only option at that point.

Using archival footage from private or public sources creates a situation where you often end up with a wild mixture of formats. In those cases we will look for “creative solutions”. As an example, we will use some material from the private video archive of the royal family as memories or flashbacks. We will give it a particular look by stylizing the footage. That way we identify it as something that is outside of our time frame or an image inside the head of our protagonist. If that is clear, the audience won’t be bothered by a different look.

Data Management and Back-Up

The SONY EX1 doesn’t use tapes; instead it records on SxS Memory Cards. Although the memory cards make the workflow more complex, it gives you the great option to review your footage instantly, and to correct settings if necessary. Those flash cards fit perfectly into regular flash card drives, like you’d find on a MacBook Pro, for instance. When we operated in the field, we always had a laptop and a 200 GB external hard drive with us. Back in the hotel we copied the material onto larger external hard drives. Since everything is in bits and bytes, you work ideally with double safety and back up everything twice: one digital back-up (hard drive) and one optical (Blu-ray disc). Again, because of the circumstances, I had to compromise and wait to come home for the safety backup. The first priority coming home was always cloning or digitizing the tapes from the V1U or F900 and copying the footage from the EX1 to a second group of hard drives.

Working with Several Languages

We tried to have the interviews in English as often as possible. Not only for the audience; it also made it easier for me. English was our official language. Even though we had a mix of nationalities on the crew, we all spoke English well enough to work together. We had an Indian line producer who translated whenever necessary. In China we usually had help from friends.

Some of the interviews had to be in Tibetan or Chinese. On those occasions we worked with interpreters who were hired for that day. When we had to take the interview in Tibetan or Chinese, we always asked the interpreter to give us a brief summary in English after the answer. But we will still need to bring somebody in during post-production who can translate for us. First we have to have transcripts with the translation. Then, during the final stages of editing, we will need to have the translator next to us in the editing room to make sure we set the cuts at the right place.

The Emotion of Language

Although reading subtitles can feel less convenient, I believe it is important to hear the original voices. So, whenever the spoken language is not English or when the English is too hard to understand, we will use subtitles. Dubbing is not an option. If you are not able to hear the original voice of a person, you are missing out on the most nuanced form of expression. Lowering or raising the voice in an emotional moment, tears that make it difficult to speak, laughter that comes from the heart…how can you try to use voice over?

Once we begin distributing DVD’s, we will add several bonus features like one or two of the interviews in full length, uncut scenes, behind the scenes footage and various languages as subtitles. We will likely select the languages based on the regions the DVD’s will be created for. It is the goal to get worldwide distribution and to find an international audience. Creating subtitles will therefore be an important part of the post-production process.

Post-Production Process

Final Cut Pro HD and a set of G5’s will be our platform for the editing process. We will use additional software for compositing and transcoding. We have just started with post-production, and we are working with such a variety of formats that we have not yet determined all the different software we will need.

We have produced quite a lot of footage since 2002, probably 400 hours or more. Most of it was shot this year. One of the reasons for so many hours in this year is the filming with two or more cameras at the same time. Of course you want to give yourself many options during the editing process for the best possible result. But having a lot of footage makes it more time consuming as well.

In order to save time, an assistant editor was logging, reviewing, and labeling some of the footage while we were still filming on the road. All the tapes from the SONY V1U were copied on DVD’s together with the time code to allow me an uncomplicated and fast review of the footage at home or while traveling. It was also a good opportunity to check the workflow, as it is our first major project with the SONY EX1. If there were to be any technical problems or logistical challenges, we wanted to find out as early as possible in the game.

Politics and Film Structure

We have several axes in the film and in the story. There is a portion of the young generation versus their leadership, the Tibetan Government in Exile. The Tibetan movement is still non-violent, but for how much longer? His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama is pursuing the idea of achieving genuine autonomy for Tibet while the Tibetan Youth Congress or Students for a Free Tibet want freedom and independence. This is the political climate Namgyal Wangchuk, our young King, grows up in. We will explore opposite positions and listen to each side’s arguments. And if everything works out, we will even have some Chinese voices in the film.

It is hard to say if there will be any changes of the original idea during the editing process. Editing has just started and the whole post-production process will take several months. But I don’t expect the story to change. Depending on whether we get to film the last few planned interviews or not, the tone here and there might be slightly different, but the story will most likely remain the same. However, the contradictions and controversy within the Tibetan community, the uprising in Tibet and the debate around the Olympic torch and the Olympic Games have created an unanticipated dynamic and more characters for the film than originally planned.

Funding and Exclusive Rights

Now that we have secured the footage and interviews, we now need more funding for the post-production. Considering the material we have and the exclusivity of some of it, I believe we will be able to find the financial support to finish it the way we want. The exclusiveness of the rights with the young King was nothing we discussed at the beginning. I think it was my commitment and my approach that formed a bond. The mutual respect and appreciation of each other came first. Then, at some point, it became clear that this film project would have to be developed over several years, and we came to an agreement that protects the interests of both sides.

Reserving rights is an important aspect nowadays. However, I believe my travel to India and my personal commitment to make this film happen long before funding was secured created the foundation we then built on. Witnessing my struggle and passion won the sympathies of the family and ultimately created an atmosphere where people get close to each other, where they forget about the camera and open up in front of it. That cannot be achieved by a contract. That has to be achieved by you personally as the filmmaker. At the end of the day it is not the paper that people trust, it is the person signing it.

Audience and Promotion

Although it is not only a film for the young generation, people between 18 and 45 years of age are our target audience. In order to reach out, we will spend some of our time in the next few months to find creative and effective ways to do so. We are already working on creating a homepage that will have details about the film and will provide background information. We might post a short clip on YouTube or other platforms to try to use every angle to promote this film.

Planning the Film’s Release

Ideally we will premiere the film no later than April 2009. Next year is full of important anniversaries: 60 years since the beginning of the Chinese invasion, 50 years since the largest uprising in Tibet and the escape of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama to India, and 20 years since the uprising in 1989. Also, people will easily remember the Olympic Games in Beijing, the protests around the world and the Free Tibet banner at the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco in April 2008. So, the sooner we finish, the better it will be for the film.

Part II:

A Filmmaker’s Notes on History and Politics

Dirk Simon with David Kaminski

The Young King’s Father

Unfortunately, I never had the chance to meet the late King in person. We spoke to him on the phone when the idea of this film was born, only a few months before he passed away. We explained the general idea and concept and he really liked our approach. He himself had suffered hugely from the Chinese invasion. Not only did he lose all his belongings and artifacts that had been in his family for generations and centuries. For his refusal to cooperate with the Chinese invaders and for his ongoing support of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, he was eventually imprisoned for twenty years. His wife and one of his brothers died in a Chinese prison camp, and none of his sons from this wife lived to become teenagers.

Despite the loss and suffering he had faced, everyone who knew him emphasized how gentle, humble, and generous he was. People loved him, and his name is still very well respected in the Tibetan community.

Meeting the Young King

I met the family and the son for the first time around the events of the boy’s coronation in June 2004. Everyone was very welcoming and we experienced first hand the infamous Tibetan hospitality. Namgyal Trichen, the son and new King, was twelve years old back then and obviously overwhelmed by what was happening around him.

He was now to carry on a lineage that is perhaps the most important one in Tibetan history. In a way, it was the end of his childhood, as he had now to follow certain rules of behavior. No more silliness in public with friends. In consensus with what His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama had told him, studying hard was now his first priority.

Questions for the Future of Tibet

When the late King had passed away, I first did not know how to proceed. The initial concept was based on his personal life. But filming a twelve year old son during the coronation, I began to understand that I couldn’t make a film about Tibetan’s past and history without raising the question of what the future will look like. I looked at Namgyal Wangchuk, the boy in King’s attire, and realized that he and his generation represent Tibet’s future. Concerns, fears, and hopes came to my mind. How will that generation move on after their most popular leader, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, is gone? What are the available strategies and tactics? Does every young Tibetan agree with the approach of his leaders?

The Role of the Young King

On his way to adulthood, our young King is facing the same questions as all the other youngsters of his generation, and one day, he will have to make a decision. How will he shoulder the responsibility to work for the welfare for the Tibetan people? Will Namgyal Wangchuk, our 16 year old King, lead or play an important role in the future? Probably, but it is hard to foresee. It is clear though, that without our help and support, the Tibetan race will be soon a footnote in human history. We have to find together a solution that guarantees the survival of Tibetans and their culture in their own land.

The Relationship between the Film Crew and the King

Besides all the hours Namgyal Wangchuk spent in front of the camera, he spent even more time with us discussing and traveling. The fact that we filmed this year with a relatively large crew of up to eight people gave him, and us, many opportunities to learn from each other. He is curious and bright. Being in contact with a mix of Swiss, Americans, and Germans has certainly broadened his horizon and increased his curiosity about the world outside India.

We discussed American politics, pop culture, and our personal lives. Interestingly, even though Namgyal Wangchuk and I have formed a strong bond and friendship, it seemed sometimes easier for him to forget the fact that we are making a film when he was hanging out with the rest of the crew. It was great to experience quite a few of his “firsts” together: his first ride in an airplane, his first espresso, and his first swim in the ocean. I never saw him so happy and relaxed as on the day he was diving into the waves of the Indian Ocean and laughing like a teenager and not like a King. Despite all of this, I was still a filmmaker who could not forget that we were making a film.

Looking at it today, this shy twelve year old will soon turn 17, his English skills have dramatically improved and he is clearly about to find his path. He is growing up. In the last few years I have been spending days and sometimes weeks with him and his family under the same roof. We have become friends in the process of making this film.

The King and an Exposure to Politics

He also accompanied us to interviews, e.g. with the Tibetan Prime Minister of the Government in Exile and with political activists. Through his participation and by discussing our film together, Namgyal Wangchuk became more exposed and aware of the various aspects of Tibetan politics and developments of the recent past. While he gave us access to his world, we gave him access to ours. I believe that kind of experience started a process that is irreversible and will continue to influence his future path.

The Struggle for Leadership

Tibetan Buddhism has one of the fastest growing communities/fellowship in the world. Many Westerners are impressed by an always-smiling Dalai Lama and his message of happiness. He is the most recognized public figure in the world. But this very successful campaign lets people in the West often forget that the reality faced by millions of Tibetans is anything but freedom and happiness.

As rightful as their struggle is, many of the techniques and strategies used are inefficient. It seems that quite a few young Tibetans in exile suffer from a loss of the sense of reality, and they pacify themselves with the hope and the belief that the Dalai Lama will fix it if anything else fails.

They divide their strength and weaken their movement by arguing amongst each other about whether the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way Policy, a compromise on Tibet’s Independence, is the right strategy or not. The political movement to liberate Tibet has been corrupted by routine and personal career management. And still today, after a 50-year effort by the 14th Dalai Lama to bring democracy to the community in exile by installing a parliament and elections, young Tibetans in exile struggle with one of the basic aspects of democracy, voting.

Tibetans are in need of a strong and charismatic leadership besides the Dalai Lama. The current Prime Minister of the Tibetan Government in Exile, Samdong Rinpoche, is highly respected but also much criticized by many of the young generation who disagree with the official policy of aiming for genuine autonomy instead of freedom and independence. Samdong Rinpoche is in his second term, and the search for a new candidate proves to be difficult. Monks have been leading Tibet and Tibetans for generations, not only in religious, but also in worldly matters. But monks have vows that bind them. And often those vows conflict with the needs of politics.

The Tibetan government receives donations and financial aid from all over the world. But how big is the support politically? Western leaders like to decorate themselves with support for Tibet when it suits them, but often without an understanding of the true nature of the issue. Being under pressure by the Chinese government and being threatened with economical sanctions, they often accept conditions that do more harm to the Tibetan cause.

An announcement by the Chinese government that they will enter negotiations with the 14th Dalai Lama and the Tibetan Government in Exile is not enough. Too often have both parties met in the last few years without any results. That much-needed dialogue needs international support, control, and guidance.

The Realities of Tibet

I believe too many Westerners know more about the cliché of Tibet than about the reality faced by Tibetans in and outside of Tibet. Tibetans have a wonderful culture and have developed an impressive religion and philosophy. But they are, after all, still human beings. They make mistakes and they can be wrong. It is time to wake up, for all of us.

The Tibetan movement for freedom is after all those years still far away from achieving its goal, but many of the local leaders are not willing to change or rethink their strategies. Some of them don’t even believe in strategies and say that they only believe in spontaneous actions. That is not how they will win the fight.

Instead of focusing on finding a way to get the world’s support and conforming to the wishes of His Holiness, they make excuses about why there is no room for alternatives. We in the West don’t even hear about most of the stuff that is happening in India. A protest here and there might make the Tibetans feel good, but if nobody in the rest of the world hears about it…let’s face it…it is basically as if it has not happened at all.

There might be a growing number of Tibet supporters in the West, but two main factors reduce drastically the opportunity and time that remains: the advancing age of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, and a growing number of Chinese settlers in Tibet who are engaged in an ongoing effort to suppress Tibetan culture and identity.

It does not matter if the movement turns violent after his death or not because Tibetans will by then have lost their most prominent leader, a man who is respected and unconditionally loved by so many around the world. Without him, without his presence, when there is nobody to whom we can give the Congressional Medal of Honor, who will care? Most Westerners support Tibetans because they love the Dalai Lama. Once he is gone, Tibetans and their movement will likely have to take a seat on the bench.

The Older Generation in Exile

The older generation in Tibet witnessed the Chinese invasion and the suffering and sacrifice of lives. The memory of having their home for themselves created an atmosphere where nothing was more important than getting their land back. They did not believe they would die in exile and were ready to return at a later time.

The Struggles of the Young Generation

Most of the young Tibetans who live today in exile were born there. The families have settled in and sometimes young Tibetans speak better Hindi than Tibetan. Young Tibetans are still very passionate about a free Tibet, but the circumstances have changed. Many flee the Tibetan settlements and dream of making it to the West or to America. This distraction is not surprising and you can see already the first signs of a detachment. Making money and having a nice life has become very important too, and who can blame them?

The first generation of Tibetan refugees took any job in exile just to survive. But this young generation needs opportunities within their own community in order to stay, or to come back.

Solutions for the Tibetans

Tibet and Tibetans will be lost without our help. Hanging up prayer flags and putting a “Free Tibet” bumper sticker on your car won’t bring any improvement. Also, there will be no change without the involvement of the Chinese government. Both sides, the Tibetan and the Chinese, complain about the tactics and hidden strategies of the other side. The Chinese say the Dalai Lama wants to separate Tibet from the Chinese Motherland. Tibetans say that the Chinese government is intentionally delaying sincere negotiations and is waiting for the 14th Dalai Lama to pass away, hoping that will bring the final solution to the Tibet issue and settle the dispute forever.

There are many sites on the internet that provide helpful information. The official site of the Tibetan Government in Exile or the site of the International Campaign for Tibet are good resources. Also, see what the Chinese government has to say. Rather than adopt another’s opinion, you should have your own.

If you want to get more involved or when you want to raise your voice, there are a few choices. You can support or participate in a local group that is active in the Tibetan cause. In addition, or if you don’t like to go on the street and protest, go to sites like www.silentmessage.org and you’ll see that basically every day you have the chance to make a difference.

I believe we need to find a way to make our political leaders understand that it is in their own interest to support Tibetans in their struggle. Politicians are very calculating and nobody will take on the Chinese government for nothing. If enough people get behind a movement, our political leadership will follow. Still, we need a solution with the Chinese in the boat, but they won’t change their policy unless there is pressure.

David Kaminski teaches TV Production/Media at Clarkstown HS North in New City, NY about 25 miles north of New York City. His students have earned five Telly Awards and over 50 national awards for their work. They also have screened their films more than 200 times in festivals across the country and internationally.

Featured in StudentFilmmakers Magazine, November 2008 Edition.

Sign Up for your own subscription to StudentFilmmakers Magazine.

- Click here to sign up for the Print Subscription.

- Click here to sign up for the Digital Subscription.

- Click here to sign up for the Bulk Subscription for Your School or Business.