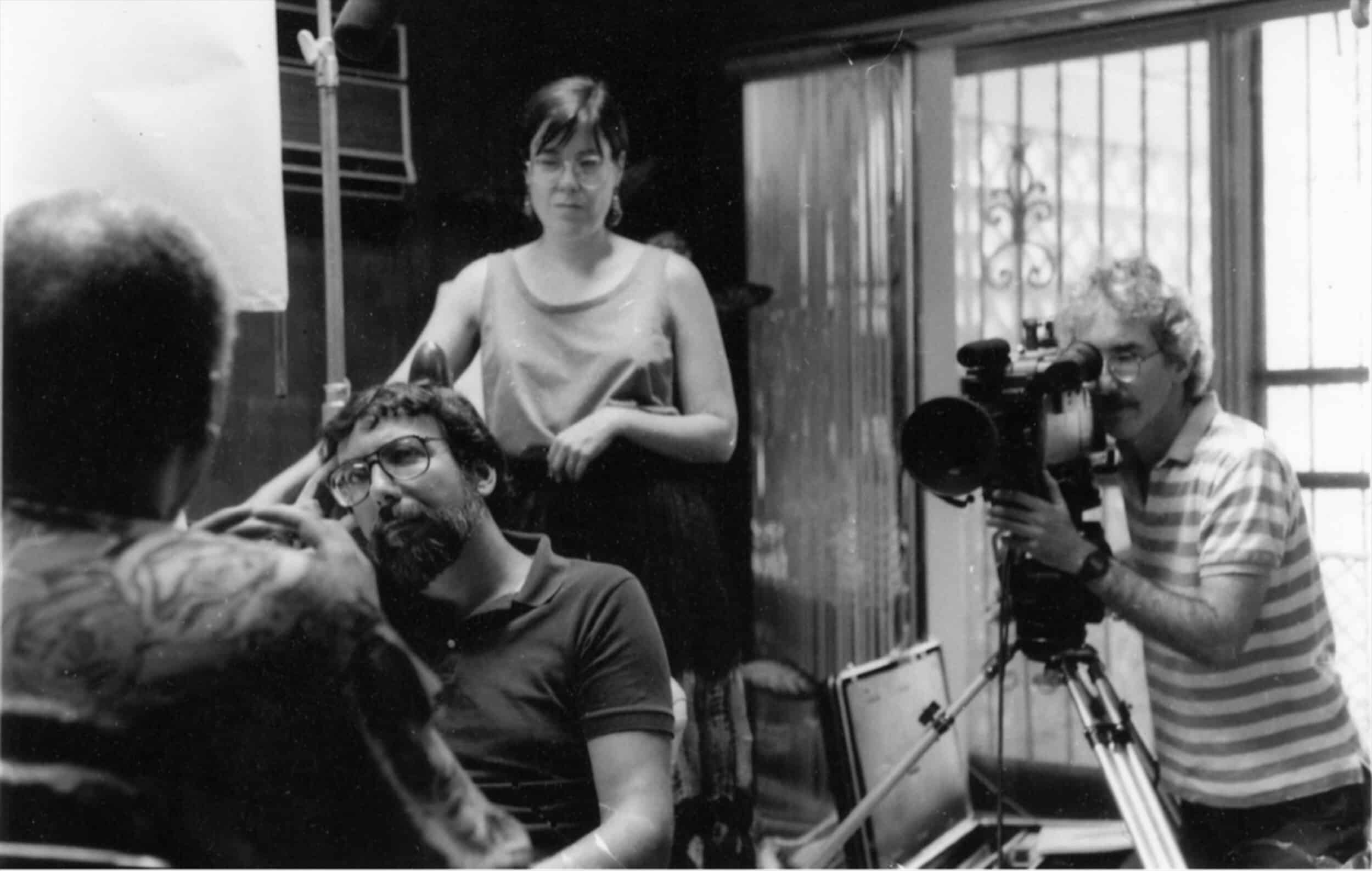

(Pictured: David Appleby (right), with Steve Ross and Allison Graham, shoots an interview for At the River I Stand.)

By David Appleby

When you’ve learned principles of photography, and the grammar and techniques of filmmaking, you are left with the questions: What do you want to make films about? Do you want to entertain, inform or comment… Do you want to work in fiction, bringing your imagination to the screen? Or do you want to turn your vision and your camera on the world around you and communicate what you find there to others?

Non-fiction has a number of advantages for the beginning filmmaker. The first and most basic is that the world is truly your stage. You don’t need to invent it, or build it. You just need to find it – something you’re interested in and want to share with others. It can be a person, a place, or a situation but it must be something you care about because it’s going to take a good deal of effort to do justice to whatever it is you wish to represent. Just like with fiction film, you will be recording pieces of the world which, when put together, give you something greater than the sum of those parts – a sense that one is participating in the world on the screen.

The second thing you have going for you is that photography seems to be able to capture reality with the push of a button – “seems to” being the operative phrase. We academics refer to this as the indexical nature of the image – its physical connection, through reflected light, to the thing being photographed. People are interested in other people and places, and if you don’t do anything to ruin it, they are willing to accept your images as real… as documenting the subject at hand… as true. This is what makes documentaries believable and trustworthy, and why it demands an ethical standard for the filmmaker.

Third, if your film turns out well, you have a much better chance of getting it seen than with a student, low budget, short fiction film. Fiction films must meet audience expectations for acting, production values, script, etc. There are expectations for documentaries as well but, if you choose the right subject, they are ones that can be met on a low budget utilizing minimal resources.

Getting started

Find a Subject

What are you going to point your camera at, and why? These are questions that all documentary filmmakers ask themselves. What are you interested in that others (assuming you are producing a piece for an audience) will want to watch? We’re all aware of the usual answers: celebrities (movie stars, musicians and politicians), exotic places, freaks, wars… and that’s fine, but as a student, it’s helpful if your subject matter is close to home. In the 1930’s, John Grierson (who coined the term “documentary”) referred to these as “films of the doorstep” – stories and subjects that are close at hand but overlooked. The filmmaker has the ability to make people appreciate their community, town, city, and the people they share those with by “making the ordinary, extraordinary.”

There are many filmmakers who find subject matter in their own families, touching on universal themes that resonate with audiences around the globe. But you don’t have to stick to family and friends. Most people would be flattered to know you’d like to make a film about them. The camera and recorder have a way of opening doors, allowing you into locations you never otherwise would have gone or been allowed to go.

It’s also true that things are said when a camera is running that may never otherwise be revealed. The camera can bring out (perhaps instigate) performances, remembrances and information that happen because the camera is running, and you get to be there as witness.

Approaches

There are many ways to approach shooting reality. In the early days of documentary one often had to get people to perform particular actions for the camera because the gear was too bulky to capture life on the go. The cameraman would have to constantly stop someone in mid action, move the camera to the next position, and have them start up again. What you’d end up with is a person acting like himself, which isn’t the same thing as “being” himself. Even so, many of these films maintained a good deal of naturalism (see “Nanook” 1922, “Night Mail” 1936 and “On the Bowery” 1957).

In the 1960’s, cameras got smaller, film got more sensitive and sound gear more portable. These innovations allowed filmmakers to observe their subjects in their natural environment in real time. The practitioners of “direct cinema” rarely asked questions or gave direction. They sought only access, believing that if they observed carefully over a long enough period of time, they would be able to capture “decisive moments,” wherein the “truth” of the situation would be revealed.

The same equipment allowed other filmmakers to go out into the world and talk to people. French “cinema verite” largely consists of conversations between the filmmaker and her subjects. When done well, the interview can be as revealing as action, and “talking heads” can be as entertaining and informative as any other form of storytelling (see “Chronicle of a Summer,” and “Le Joli Mai”).

The majority of documentaries are hybrids of these earlier forms, covering action in a direct manner (contemporary or archival) and either intercutting interviews or using them as voiceovers.

Narration

So many documentary films have used a “voice of God” narration that it can be hard to imagine one without one. These voices are often those of well known actors – people who can bring a quality vocal performance along with some added cache and credibility. Early documentaries that were filmed silently needed this voice, added in post-production, to convey necessary information. And as television grew out of radio broadcasting, it was natural for the voice to be given primacy. Narration continues to be used in the majority of documentaries and you shouldn’t shy away from using it if the alternative is to not get your message across. Like any other writing, narration is an art and can be done terribly or well. If it attempts to convey too much information, or is redundant, it can be awful. Many “boring” documentaries can be blamed on bad narration. But the right words at the right time can be the difference between a sequence that works and one that doesn’t.

Ideally, the narration should emerge naturally from the footage and the experience of making the film. To write narration beforehand, and film solely to illustrate what you have written, works in some situations but avoids the documentary experience – the process of exploration and interaction with the subject that the filmmaker goes through before expressing the result of that process through their film.

The Interview

If you are going to do a formal interview, you should pay attention to and practice the following :

Don’t pre-interview. Very few people are as engaged – or engaging – when telling you a story for the second time. Talk to your subjects in generalities when you are discussing what you may be talking about but avoid falling into the interview before the camera is rolling. It’s perfectly alright to say, “That’s really interesting, but let’s save that story for the interview.”

Let the interviewee know what they’re in for. Tell them the size of the crew, what equipment will be used, that some furniture may have to be rearranged to get the best shot, and how long the process will take. If your presence is an unpleasant surprise, it will negatively affect the result.

Prepare well. Know what you want the interview to accomplish but don’t be afraid to follow other tangents that emerge from the conversation.

Have notes to remind you of things you want to cover but NEVER LOOK AT THES

E NOTES WHILE YOUR SUBJECT IS TALKING! Eye contact is extremely important for any conversation.

Don’t begin asking the next question as soon as your subject stops speaking. Maintaining eye contact and waiting can result in the continuation of a thought, providing fresh insights from the interviewee.

Questions should be asked in ways that discourage short replies. “Can you tell me how you were feeling at the time?” is better than “Were you scared?”

Don’t be too quick to wrap the interview. It’s very common for the subject to come out with their best material while the crew is striking and the pressure is off. When you think you’re done, keep the crew and equipment ready so, if this happens, you can say, “That’s terrific, let’s roll and get that on tape!” If the subject remains seated at the end of the interview, keep the camera rolling. You never know.

Where should the interview take place? Obviously it should be in as quiet a place as possible and either relate to the subject matter or, at least, not distract from it.

It’s always safer to light an interview than to use daylight. Sun and sky are not consistent, making editing difficult. This is especially true for long interviews.

Pick a chair for your subject that won’t allow them to rock, pivot or slouch.

If possible, sit your subject away from a wall. Room behind them will allow shadows produced by your lights to fall unseen below the frame. Not having a close, flat background will also add some depth to the shot.

Keep the camera position as frontal as possible. Obviously, you can’t be directly behind the interviewer but you want to be just far enough off axis to allow for a clean MS, and CU. (or an O/S MS and a clean MCU and CU.)

Remember that the lit, sit down interview is an artificial situation and may be uncomfortable for some subjects. If you find this to be the case, you can interview someone while they’re engaged in a common activity. The fact that the subject is doing something familiar may make all the difference in their comfort level while speaking. This may present some audio problems but it can be worth it in terms of content and delivery.

Reaction shots

If you’re doing a piece in which the interviewer is also a “performer” (think 60 Minutes or Barbara Walters), then you will want shots of them asking questions, and reaction shots listening and responding non-vocally to answers. Having the interviewer on camera allows the audience to see who is asking the questions and the reaction shots can be used as cutaways to cover edits in the conversation. This can be accomplished by using two cameras, or by moving the camera after the interview and getting the needed shots of the interviewer repeating the questions and reacting (a very common ploy of journalists on single camera shoots).

If you want the interviewer to remain off camera, but want their questions in the show, be sure to mic both people – recording them on separate tracks. If you don’t plan to use the questions in the final film, you may want to record them anyway just in case you get a great answer that requires the question for context. If you have only one mic, you can still use an occasional comment from “off camera” but the quality will be greatly reduced (actually, this can sometimes be a very effective device).

Coverage/ cutaways

There is no such thing as getting too much cutaway material related to your subject. Any images you can shoot, scan or download that can illustrate what your narrator or interviewees are saying will be invaluable in post-production.

Reenactments

Reenacting an event can be a very useful means of illustrating what occurred at a time when the camera wasn’t present. The events portrayed may have occurred earlier that day, a year ago, or hundreds of years earlier. These portrayals will “stand in” for the original activity and will probably be perceived as such by the audience – as an exact account of what occurred. This puts the onus on you to get it right. Because memory and records may be faulty, and documentarians tend to have points of view that they bring to the “performance,” many filmmakers frown on using reenactments, seeing them as contaminating the reality being conveyed.

Sound

You can mic the interviewee with a boom or a lav.

The boom provides the most natural sound. It can be held in place with a C-stand but needs to be repositioned by an operator if the subject leans forward or changes position in any way. As usual, bring the boom in from the fill side to avoid shadows in the shot.

A lav has a closer perspective than the directional mic on a boom but it rejects background noise better. While the lav can be hidden, you risk clothing rustling and they are so small now, and used so often, that audiences don’t seem to mind them being in the shot.

Editing the interview

If the interview is to be a primary source of information, contributing more than a line here or there, it needs to be cut so that information is conveyed smoothly and clearly. Doing that almost always entails multiple edits to cut out pauses – vocal (um, ah) or silent – and to keep points as concise as possible.

I suggest cutting the material for your ear first. Forget about the picture and edit it as if it was a radio interview. You’re not changing the meaning of what was said. Rather, you are molding the material into an articulate, efficient track that delivers information and emotion efficiently, something that the interviewee did not have to do during your conversation.

Depending on the style and structure of your film, place the interviews where they are needed. Because they were cut for audio only, the image will be a long series of jump cuts that, in most cases, you will want to disguise with cut-away material – sometimes referred to as “B-roll.” This material should feel natural to the subject being discussed, rather than looking like a band-aid to hide a jump cut. If this is done well, the information will be conveyed smoothly and no one will know that the interview has been altered. As long as the meaning of what was said remains the same you shouldn’t have any ethical problems with this practice, but it’s always good to remember that anything you manipulate, while creating something that proposes to be “real,” is rife with ethical issues that you should be concerned about.