How to prepare, shoot, and live to tell the story…

by David Lent

You’ve been on an airplane for what seems like an eternity. Anybody wearing a smile got off at the last stopover. You’re jetlagged, hungry, exhausted and afraid. No one speaks English and the locals are edgy. You’re carrying an obscene amount of cash in a desperately poor country. You’ve got a live shot in six hours, no time to eat or sleep. If you hadn’t realized it by now, you’re in a world of trouble. Many media professionals entering a conflict region for the first time don’t have a clue about the dangers awaiting them. They work and survive on their wits, often paying a heavy price for lack of preparation. The Committee to Protect Journalists documents more than 600 attacks on working media professionals each year. So we must arm ourselves with better security awareness and survival skills.

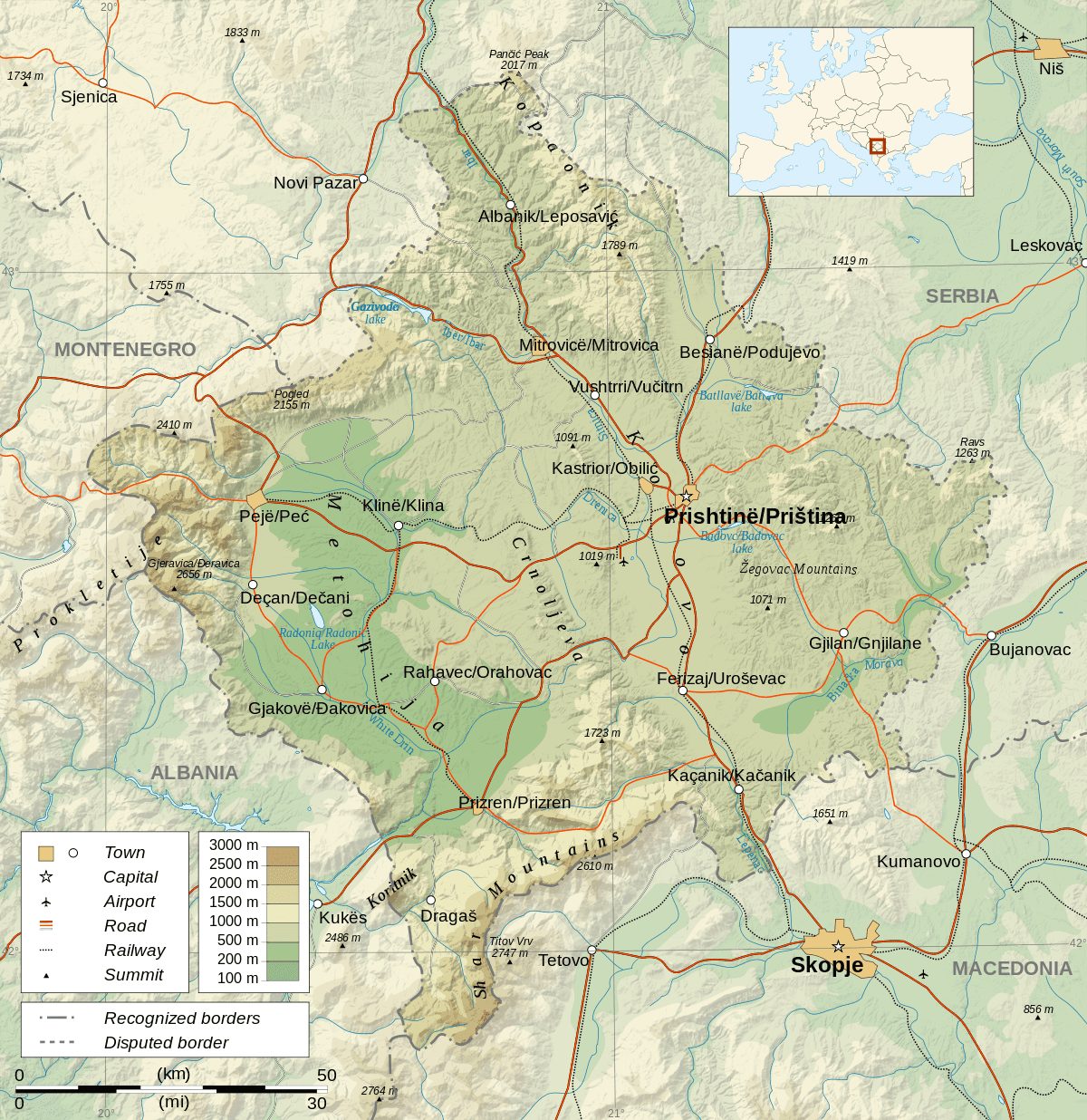

There are a lot of bad places to be an American cameraman. One of the worst for me was the Balkans in the spring of 1999. As 300,000 Kosovar refugees poured across the Macedonian border and NATO bombers hammered Belgrade, I packed my gear and made my way to Skopje, Macedonia’s capital. I intended to hook up with one or more American networks and make a bundle of money, as I did during the first Gulf War. I seriously misjudged the employment opportunities, yet found myself immersed in a menacing story all but ignored by western media. I decided to stay and make a documentary.

The locals were edgy. When I was recognized on the street as an American, the typical greeting was: “F— YOU!” I was chased from a restaurant by a local thug, spat upon by a border guard, and pursued by drunken protesters. I became suspicious of everyone and immobilized by fear. I decided to adopt a quote from Nietzsche: “Go joyfully into the horrors of the world.” This mantra, combined with the dozen or so amulets I wore, helped me muster the courage to finish my doc.

Threats

In a region where tribal, religious, or nationalistic fever is high, where famine or fighting has crippled civil society, threats are everywhere. They arise without warning. How effectively you respond to sudden danger will depend on your preparedness. By visualizing the various possible scenarios and rehearsing a response, you are far more likely to keep cool and focused on appropriate action. Some threats to consider include:

- Drunks

- Thieves

- Robbers

- Hijackers

- Firefights

- Angry mobs

- Armed thugs

- Kidnappers

- Snipers

- Terrorists

- Martyrs

- Traffic Accidents

- Hostile demonstrators

- Bribery, Corruption

- Poorly trained police and militia

- Falling bullets from celebrations

- Ear damage from explosions

- Unexploded ordnance

- Collapsing buildings

- Friendly fire

- Land mines

- Booby traps

- Disease

- Contaminated Food or water

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Preparation

The more prepared you are for high-risk environments, the better your chances for working safely, effectively – and living to tell the story.

Talk to people who have been to the region, especially media professionals. Their personal experiences will alert you to the realities of a new place and the nature of the conflict. They may be able to supply local contacts and help you find accommodations.

Use your contacts to identify a driver and/or translator who speaks your language and can be trusted with your security on the ground.

Learn about the culture, including history, traditions, music, customs and local etiquette. Study maps of the country and region. In many countries you will make friends merely by speaking a few words of the local language.

Put personal affairs in order, including a will and a farewell letter to loved ones. (Plan for the best, prepare for the worst.)

Get in shape for a lot of hiking and running.

Get vaccinations you may need (malaria, yellow fever, etc.).

Consult the U.S. State Department and other background-relevant websites.

Anticipate conditions particular to the region: dust, heat, humidity, cold, rain.

Equipment to Pack

Be a step ahead of airport security. A case full of gear can complicate and delay travel. Many agents are unfamiliar with fragile lighting, audio and camera gear. They will remove carefully packed items then stuff them back in their cases to be easily broken or damaged in transit. Consider packing fragile equipment in your carry-on.

In or near a conflict zone, conditions change quickly. You may need to move suddenly, taking only what you can carry. Always pack simple, compact and light. I’ve learned this lesson over and over again but learned it especially well in Kuwait City, just after coalition forces liberated the country. My reporter secured a room at a high-rise downtown hotel, but there was no electricity, hence no elevators. Twice a day I hauled my gear up and down thirteen flights of stairs.

Make inquiries. Will there be regular access to AC power? Gasoline? Sufficient food and bottled water for the crew? Internet access? Fax machine? Cell service or a landline?

Plan for power. Charging cell phones, laptops and camera batteries can be a major challenge in developing countries. Pack at least a full day’s worth of batteries and all the adaptor plugs needed for the countries you plan to visit. You may want to invest in a solar charger.

Take only essential gear and backup: camera, camera support, batteries and charger, recording media, audio and lights. Depending on the destination, consider these additional items:

- Maps of the city and country.

- Flak vest if fighting is anticipated.

- Mobile phone that works in-country.

- Equipment manuals.

- Equipment repair kit.

- Camera raincover or garbage bags to protect gear from rain, snow, dust, or sand. In desert conditions, put gaffer’s tape over vulnerable openings on the camera.

- Stick-on heavy-duty Velcro hook and loop for attaching accessories to your camera and other equipment.

- You’ll be turning knobs, wrapping cable, and schlepping gear until your fingers are nearly raw. Bring a pair of the thinnest gloves you can find, allowing the soft touch required for camerawork.

Travel inconspicuously.

Ship the fewest number of equipment cases necessary. Be especially vigilant about your luggage in or around travel hubs – airports, train and bus stations – where theft blends with the chaos.

Personal Items to Pack

- Photos that reveal your personal life: family, friends, home, pets. They go a long way toward crossing barriers in strange cultures. A picture of his family saved a CBS producer’s life in Iraq.

- Small, inexpensive gifts. Stickers or flag pins for little kids and a useful item for adults. (Expect enormous hospitality.)

- Good luck charms and amulets. In a war zone, you will become superstitious and religious.

- Clothes – 3 changes of shirts, pants, underwear and socks – appropriate for the climate and local culture. Sunscreen and hat for desert or tropics.

- A laminated card with phrases in the local language. “Don’t shoot!” is a good one to know.

- First aid kit.

- An ample supply of medicines you may be taking.

- $200-300 in local currency for a taxi, a meal and a place to stay your first night.

Personal Security

Think first. Think through in advance what you will say or do in potentially life-threatening situations. There may only be time enough to react, not debate.

Divide and Hide. Keep a stash of cash – ones, fives, tens and twenties – divided among four or five envelopes, concealed in discreet places. One might be gaffer-taped to the bottom of a battery charger, another slid into an opening you cut along the edge of a piece of protective foam, and another buried among gels and diffusion. A typical thief is: (1.) in a hurry, and (2.) ignorant of and not interested in low tech video accessories.

Be alert. If you are approached by people you don’t know who want to set up a meeting or offer access or information you covet, arrange to meet at a public place. Do not go alone. Tell someone you know and trust where you will be and when you expect to return – and who to call if you do not.

Rip-offs. In the eyes of many poor or war-distressed people, Westerners with electronic gear = money. Either accept that there will be “surcharges” or have a local do the buying for you.

Carry these essentials:

- Permit to shoot in the country, typically from the Information Ministry.

- Copy of passport (leave original in hotel safe or with concierge).

- Contact numbers: U.S. Embassy. Your family. Local hospital. A technician who can troubleshoot equipment problems and supply backup equipment.

- Picture IDs. My Maryland driver’s license, with its eye-catching hologram, got me through a checkpoint in Saudi Arabia simply because it was the most sophisticated-looking piece of plastic I had.

- Your business cards with a local contact number on the back.

- Map.

- First aid kit.

- Flashlight.

- Small binoculars.

- 3×5 cards (for a white balance and to jot down names and information).

- Medical info (allergies, blood type, medications you must take).

- Moist towelettes (You will never have enough).

- Bottled water.

DO NOT carry these:

- A weapon of any kind.

- Illegal drugs.

- Passport, credit cards, a lot of cash. In some situations, press credentials can be a liability. Consult with local colleagues on their experiences.

Safety and Security While Traveling

As I was arriving at the Khartoum airport for an assignment in Sudan, a customs official demanded a $600 “deposit” for my camera, promising that the money would be returned prior to my departure. When my producer and I returned to the airport to collect the deposit, we were taken on an endless walk along the tarmac. It became obvious that if we continued to press the issue we would miss our flight. Unless you’re content to kiss the money good-bye, refuse to pay or attempt to negotiate a lower price. Such officials are often freelancing for extra cash and may want to avoid a scene.

Settling In

No starch, please. Consider staying in a private home rather than a hotel. On the several occasions I’ve done this, doors have opened to family, friends, and neighbors who have led me to opportunities, interviews and valuable information. A private home typically costs much less than a hotel, is often more secure, and your movements are less conspicuous. My host in Skopje, Macedonia, cooked for me, did my laundry, even ironed my underwear – at no extra charge.

Never travel alone in a conflict zone. Arrange for a trusted driver and/or translator who is familiar with the area and potential trouble spots. A driver can also act as a guide and/or bodyguard. Be sensitive to their perspective. Immersed in the conflict, they will have different ways to gauge the degree of danger and the character of local sentiment – especially toward the media.

R&R. If possible, avoid scheduling a heavy workload your first day in-country. You’ll need rest, especially if adjusting to jetlag. In general, sleep when you can.

Get down with the locals. Eat, socialize and watch local TV to better understand the culture and unfolding events. Ask for guidance from local contacts, such as experienced media colleagues or embassy staff.

Local Customs

Love yer Mercedes! In some cultures, if you admire something the owner may feel obligated to give it to you. Or it may be unwise to use your left hand to greet people or eat food. In many parts of the world, it is a deep insult to cross your legs so the bottoms of your shoes face your companion. While riding in the back seat of a car with a Saudi producer, I learned that if we were spotted by the Mutawa – the religious police – she would be arrested for being in the company of a male who was not her husband or relative.

Shooting on the Streets

What you lookin’ at? In the more dangerous neighborhoods of the world, you may encounter people who suspect you are there to make them look bad. An expensive camera and an obviously rich, by local standards, Westerner can be the easiest and most convenient target for unemployed, hopeless or aggressive locals. Poverty and war-related depravation breed shame and resentment. Imagine how you would feel if the situation were reversed. Engage people; let them know what you want to shoot and why. Consider carefully if the shot is worth the emotional and security costs to them and to you.

While walking in Skopje, Macedonia, camera on my shoulder, pulling a cart that held my Domke bag, I felt a slight tugging, the kind you feel when a fish is nibbling at a baited hook. I turned to see two kids poking their hands into the pockets of my runbag. At the urging of my translator, I gave them each a small amount of money. This gesture converted them from predators to partners, and later they allowed me to shoot video of them working their hustle in a public square.

Protect your key asset. When loading equipment into a vehicle, put the camera in first, then the rest of your gear. At the destination, remove the camera last. In a restaurant or café, keep the camera in your field of vision at all times or, if appropriate, on the floor next to you. Keep the shoulder strap around your leg and your foot always in contact with the camera.

Keep a low profile. Avoid using your camera light at night, especially in crowds. You’ll attract attention and risk becoming an easy target for theft or assault. Be cautious in crowded public spaces. Enlist your translator, driver, or sound recordist to watch your back. If something doesn’t feel right, leave the scene quickly and inconspicuously.

Avoid deserted streets at night. If you can’t, then walk with confidence. Do an occasional 180-degree turn so you can spot potential trouble from a distance and revise your route accordingly.

Beware – be very aware – around military activity, especially if you lack official permission to shoot. With night vision binoculars and telescopic sights, they will see you long before you see them. They may be young, poorly trained and easily frightened. They may not see you clearly. They won’t hesitate to shoot if they feel threatened by that dark, potentially menacing metallic object over your shoulder.

While covering the Kosovo refugee crisis in theBalkans in 1999, I positioned myself across the street from the American Embassy in Skopje, Macedonia, to get a variety of wide and medium shots – the embassy had been stormed by demonstrators a few days earlier. I zoomed in to two marine snipers on the roof, engaged in what appeared to be housekeeping chores in their camouflaged perch. On the telephoto shot, I could see one of the soldiers aim his rifle at me. I yelled, “Hey, I’m an American!”– and ducked behind the nearest tree. To this day I don’t know if he mistook my camera for a weapon or was just messing with my head.

Unless you have permission, shoot military bunkers, camouflage tents, checkpoints and fighting from the farthest distance possible. A good telephoto lens can give you the shots you need. Before you shoot, plan an escape route. You’ll have some serious explaining to do if you get caught. If gunfire erupts nearby, hit the ground and find the nearest cover.

The Old Switcheroo. Keep an unpackaged blank memory card, disc or tape concealed on your body. If you’ve shot something sensitive, police or a security guard may attempt to confiscate the material. If it feels safe to negotiate, refuse to give it up. Or try misdirection: Have another crewmember attract attention while you conceal and replace the recording media, before it becomes a bigger issue. This has worked for me in several situations.

I can recall a hilarious scene in the 1967 dark comedy/anti-war film, “The Dirty Dozen.” Major Reisman, an irreverent Army officer played by Lee Marvin, enlists the loveable but misunderstood goofball Pvt. Vernon Pinkley (Donald Sutherland) to impersonate a General, as part of Reisman’s elaborate charade to humiliate his bitter adversary, Colonel Breed (Robert Ryan). While “General” Pinkley (Sutherland) is inspecting a platoon, his eyes light up as the potential for mischief sinks in. He stops to regard a baby faced young soldier.

Pinkley: “Where are you from, son?”

Soldier: “Madison City, Missouri, sir!”

Pinkley: (long pause) “Never heard of it.”

A similarly comical, but edgy, scenario unfolded on a news assignment in Honduras for a Scandinavian client. The story focused on the escalating conflict between an organized local resistance group, known as MAU, and a powerful lumber syndicate. In spite of a government ban on logging in the region, illegal deforestation has continued with impunity, leaving entire towns and villages without wells for drinking water and chronic food scarcity. Recent assassinations and reprisals had turned Olancho into a dangerous neighborhood.

The producer and I, accompanied by our translator and a driver, left our motel in Juticalpa one morning to drive the now familiar ten miles of paved road to the intersection of what was wryly referred to by locals as, “The Highway of Death.” This bumpy, dusty, winding road was one of only two ways to get into or out of Olancho, which is heavily traveled by logging trucks. On this day, a roadblock had been set up to search passing vehicles for illegal drugs and weapons. The producer wanted shots of the National Police, who had been accused by MAU of being in the pockets of Big Lumber and complicit in the killing of several resistance leaders.

Conditioned by experience to be wary of shooting military checkpoints without permission, I used my Steadybag and the hood of our pickup truck to grab some covert telephoto shots. After a half–hour of cooling our heels in the pickup, hoping the soldiers might eventually warm to our presence, our translator – whom I will call “Maria” –left to have a quiet word with the unit Commander.

Five minutes later, she returned with the welcome news that we had permission to shoot whatever we wanted. Barely able to suppress a giggle, “Maria” recounted the conversation: “I told him I worked for the Security Ministry, that both of you belonged to a U.S. Government agency in Washington, DC, and you had traveled to Honduras to verify that the National Police are properly inspecting the permits for log transporting trucks.” Thanks to “Maria’s” quick wit and audacity, the Commander decided that our “mission” was in his and Honduras’ best interest.

After ducking into the command post, the Commander reappeared in a freshly pressed, medal–decorated uniform, ready for his close-up. I could now move freely among the soldiers and shoot the searches. As luck would have it, the next vehicle stopped at the checkpoint yielded an impressive collection of large caliber handguns.

Don’t take sides. In war-torn or distressed regions of the world, there is no shortage of desperate, angry and dangerously stupid people. Get to know your subjects and resist the urge to view them as the enemy. By being open, you will reduce tension and people may open doors for you – sometimes big doors.

Keep left. If you find yourself shooting a firefight on a city street, stay on the left side; this allows you to keep your body concealed in a doorway or alley, exposing only the camera (and your right arm).

Shake it off. In conflict zones, things can happen quickly and fiercely. Nerves become frayed, relationships strained. Unresolved anger is toxic to teamwork. So fight when you must, then shake it off and get ready for the next move. Your lives may depend on it.

Plan for the best, prepare for the worst. Think through every conceivable scenario. How will you react if this or that happens? If you’re entering a conflict zone, decide how you’ll get out quickly and safely. Trust your experience-bred instincts.

If your assignment puts you in close proximity to American troops, consider writing your blood type on the outside of your boots or shoes. U.S. troops do and that’s where a medic will look first.

Personal Security

Never carry a weapon into a conflict zone or travel with a colleague who does. Do carry small bills in the local currency, cigarettes, or inexpensive gifts to smooth your way through checkpoints or with edgy locals.

Hide most of your cash and a copy of your passport on your body. Keep $100 in your wallet to grease your way out of a tight situation.

Bodyguards can be a blessing or a curse. If you hire a local for personal security, check him out carefully ahead of time. The more you know and trust him, the better you will be able to focus on the work.

Flak jackets may be necessary at times; yet wearing one can put distance between you and the unprotected people you’re filming. Weigh the advantage: being one of them or being a target by being one of them.

It was after midnight at a Quranic School for homeless Sudanese boys on the outskirts of Khartoum, after a brutally hot day of shooting followed by a long drive. The temperature had mercifully dropped below 100 degrees, but hours had passed since I foolishly shared the last of my bottled water with our driver and a minder from the Information Ministry. Feeling the ominous symptoms of dehydration, I gratefully accepted an offer of a Pepsi from our hosts, which was delivered, to my alarm, poured in a glass filled with ice cubes – made, I was certain, with water I had been warned to avoid at all costs.

My common sense, now impaired by the lack of fluid intake, failed to sound the alarm. I deceived myself by thinking, “If I drink this Pepsi fast, before the ice melts, I’ll be fine.”

Fortunately the symptoms of E. coli didn’t present themselves until I returned to California and was able to receive prompt medical attention.

Coming home.

When you return home after exposure to danger or trauma, don’t expect many in your family or among your friends to be willing to listen. Seek professional counseling.

War is dirty. F—–g dirty. Being a professional witness to violent conflict or inconsolable suffering is not for the faint at heart. You will come face to face with madness or agony that you can’t stop, can’t fix, and can’t reconcile. Yet if you will ignore the big picture, focus on the task at hand and remind yourself that misery is always optional; these assignments present extraordinary opportunities to make a difference. By just showing up with a camera to illuminate the darker corners of society and human nature, neither will ever be the same.

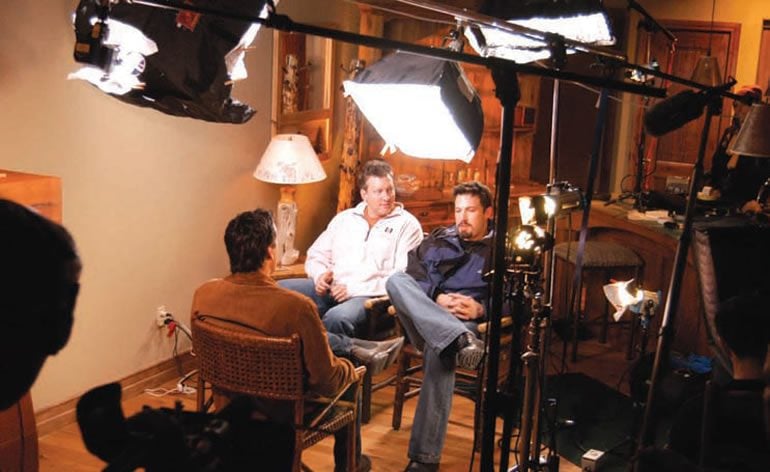

Photo courtesy of the author.

David Lent’s career in television spans forty years. David co-produced and shot the critically acclaimed PBS special, “Life Without…Inside San Quentin.” With Susan Burgess-Lent, he co-produced the documentary feature, “Staying Alive,” based on Studs Terkel’s best seller, “Working.” David currently works as a news and documentary cameraman for numerous domestic and international clients including BBC, FOX News, Al Jazeera, YLE, and ARD. David Lent’s new book, “Video Rules,” is available in December on paperback or download at: www.daveandcompany.us.