by M. David Mullen, ASC

Often I get asked what a cinematographer does in pre-production, especially on a low-budget feature production. The short answer is “as much as possible.” One can never prepare enough, or at least, I’ve never found myself wishing I had less time for pre- production.

When I started out shooting features with budgets under one million dollars, the shooting schedules were typically 18 days (three 6-day weeks) or if I was lucky, 24 days (four 6-day weeks). On such projects, interviews for DP candidates usually begin a month in advance of shooting, and the DP might be offered one week of paid prep, maybe two, whether or not he or she invests more time than that (which the DP normally does.) It’s difficult on a low-budget production to enlist a DP much earlier than a month in advance, for two reasons. One is that often a production doesn’t have the money in place until that time, and therefore, it is hard to ensure that shooting will actually occur on the dates planned; also, many cinematographers won’t commit to a small, low-paying project far in advance because they want to keep their options open for higher-paying jobs until the last possible moment. But obviously at some point, a DP has to commit in order to put in enough time for prep, which is precious. So there is something of a conundrum here – a low-budget movie would benefit from extensive pre-production, perhaps even more so than a big-budget movie, but does not have the money to pay people to work far in advance nor get commitments from cast and crew before their financing is in place, and once financing is in place, there is a rush to shoot before such financing can evaporate. As one director/producer once told me, “you can have everything in place except the money, but if you don’t have the money, you don’t have a movie.”

So on most small movies, a DP will work off and on for roughly a month in pre-production, despite only being paid for a few weeks if that. It’s not particularly fair, but many DP’s would rather have the prep no matter what once they are committed to the project. And a month is barely enough time. You can figure, working backwards from the first day of shooting, that the last week of pre- production will be taken up by three important events: the production meeting where all the department heads go through the script scene by scene (sometimes an all-day affair), the tech scout, where the department heads visit the locations, (this can take more than a single day if there are a lot of locations separated across town), and then the equipment prep & pick-up days. For a DP, this may also include any tests needing to be shot.

During that week and the previous week probably, the director will probably have every available minute taken up by casting issues and rehearsals, if lucky. So that leaves the weeks before the final two weeks for the cinematographer and director to sit down and discuss the script in detail, working their way through every scene, tossing out ideas. These discussions may even lead to some script rewriting because some logistical errors may be discovered or ideas for scene transitions may need to be written down. These meetings are very intensive, and I’ve found over the years that at the most, they can only take up half a day, four or five hours at the most. Partially because you still need the rest of the working day to deal with production office needs, (interviewing crew positions, coming up with equipment lists, etc.), but mainly because at this point you are often still scouting and may have to drive around in the afternoon to look at potential locations.

So usually I’ll ask the production office, AD, or director’s assistant to schedule a regular morning meeting between the director and myself in a block of three or more hours. And in this time, it can easily take three weeks to get through the entire script if the scenes are discussed in great detail.

At this point, I may take all my meeting notes and draw up shot lists or draw them out as storyboards. However, with most of my time spent doing the typical pre-production work of a cinematographer, my free time to draw storyboards is limited, so I will concentrate on selected scenes, or convince the production to hire a storyboard artist so that I can just turn over rough sketches to save time. I know that a DP who can also draw storyboards is not typical, but I find it a very useful skill.

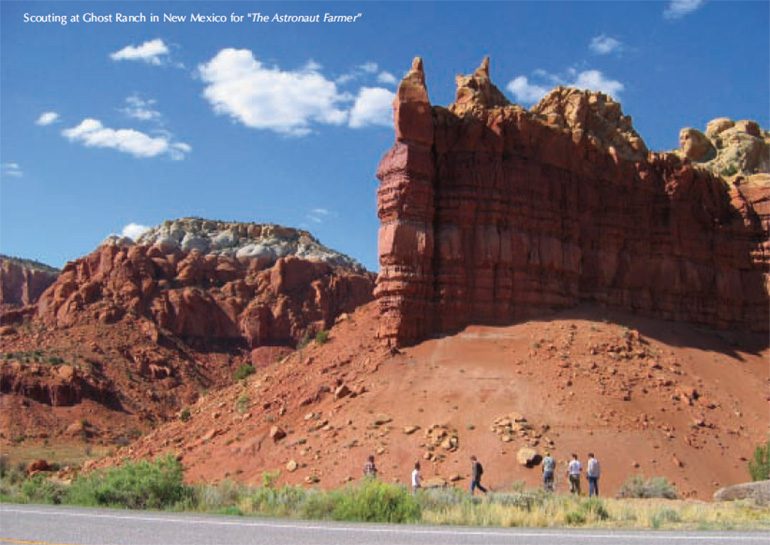

In regards to location scouting, my main advice is: don’t settle on an important (storywise) location that doesn’t excite you in some way, that doesn’t inspire you photographically. When there are a lot of locations to be found, there is the pressure to lock something in early so that time can be spent looking for the next location, which is understandable. But if the location is not photographically interesting plus is difficult to shoot in, and you sense that there must be better alternatives out there, try and hold out for something better, within reason.

This brings me to some great advice I once got from Allen Daviau, ASC, when I was first starting out. He said, (I’m paraphrasing), “know your first week of shooting as thoroughly as possible, down to the finest detail.” In my limited pre-production time, I am as over-prepared for the first week as possible, down to knowing where most of my lights are going to go. I find that it helps the crew’s morale when the first weeks goes like clockwork, it sets the right tone for the production, and it allows you to set the look of the movie in great detail. Obviously it would be great to be that prepared for all the weeks of shooting, but in reality, often things start changing by the next week – scenes are rewritten or dropped, the schedule is changed, and as a DP, you find yourself more in a reactive mode of dealing with the daily work in front of you. At this point, by the second week, it matters more that you have a sense of the sort of pace that you can work the actors and crew at, what the challenges of the location and weather are, and that you have a good plan for any complex sequences coming up. But for more ordinary dialogue scenes, you find yourself falling back into the traditional block-rehearse-shoot formula, where you work out the coverage based on the blocking of the actors, and the amount of time allotted to shoot the scene.

Hopefully, the bulk of your pre-production time will be spent with the director. But besides that work, you will find yourself in many meetings with the line-producer/UPM, working out the equipment package details, shooting format issues, post workflow issues, (hopefully the editor will be hired at this point so they can be involved). You’ll be having meetings with the art department people, in particular the Production Designer, discussing color schemes and photographic concerns you have. And you’ll be working with the Assistant Director to make sure that the shooting schedule is practical from a cinematographer’s perspective.

My final comment is that there is always a high level of anxiety before a production if you truly care about the quality of your work. But most of this fear is the fear of the unknown. I’ve found that once the scene is broken down into its elements and I understand where the camera will (and most importantly, won’t) be looking, how many shots are needed, giving me an accurate sense of the work involved, I can breathe a little easier and address the problems in a more focused and efficient manner. It comes down to the old truth that an editor told me about setting up his work space, (this was back in the days of flatbeds and trim bins, etc.): “The more organized you are, the more creative you can be.” Too many students worry that being prepared will somehow make them less artistic on the set, but the opposite is true. The creative mind that carefully breaks down a scene visually while sitting relaxed at home will come up with a different set of ideas than the one working quickly and reflexively on the set to an immediate problem, so being prepared only increases the number of ideas you’ll get to consider on the set. You may ultimately decide to chuck your pre-production concepts once on the set, but at least you’ll have that luxury.

David Mullen, ASC, was an Independent Spirit Award Nominee for best cinematography for Twin Falls Idaho in 1999 and for Northfork in 2003. His filmography consists of over 30 film titles, including Akeelah and the Bee (2006), The Astronaut Farmer (2006), and Shadowboxer (2005).