HOW-TO, Techniques, & Best Practices Channel

| Insights into Lighting and Shooting HD - Exclusive Interview with Thomas Ackerman, ASC - Cinematographer for Balls of Fury By Staff posted Jun 30, 2009, 16:24 |

Check out this article in the print edition of StudentFilmmakers Magazine, February 2007. Click here to get a copy and to subscribe >>

Insights into Lighting and Shooting HD:

Insights into Lighting and Shooting HD:

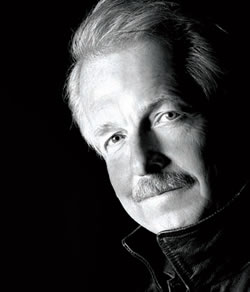

Exclusive Interview with Thomas Ackerman, ASC

Cinematographer for "Balls of Fury"

Cinematographer Thomas Ackerman, ASC is best known for his work on Jumanji, Tim Burton’s classic Beetlejuice, and National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation. With a filmography of over 30 titles, Ackerman has worked on a wide variety of films, lensed the box office hit comedy, Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy, the hit comedy, Are We There Yet?, and more recently, The Benchwarmers, Scary Movie 4, and action/sport/comedy, Balls of Fury, to be released in 2007.

In this exclusive interview with StudentFilmmakers magazine, Ackerman details his work on the upcoming HD feature, Balls of Fury, and discusses lighting and shooting with the Panavision Genesis system. He also reflects on the challenge of photographing comedies, candidly addressing the question of whether it is possible to “shoot funny.”

StudentFilmmakers: How did shooting with the Genesis for Balls of Fury effect lighting? Could you describe the lighting for particular scenes?

StudentFilmmakers: How did shooting with the Genesis for Balls of Fury effect lighting? Could you describe the lighting for particular scenes?

Thomas Ackerman, ASC: From the get go, Balls of Fury was an ambitious project. It was a kung fu, ping pong comedy with a big action component. There were lots of sets, martial arts, and obviously, a huge amount of world-class ping pong that was the crux of everything. There were stunts, gun battles, rain scenes (now cut out of the final version) … Although, fortunately, no animals or little kids. But on an 8-week schedule, it was a bit daunting.

Fortunately, Ben Garant and Thomas Lennon, who wrote the film and co-produced, had a rock-solid partnership and a sense of assurance that put all the challenges into perspective. Plus, they love shooting movies. Every day began with a wonderfully detailed rehearsal for the crew. Ben would go through the scene with the actors and the feeling was, no matter how much work was scheduled that day, it was all going to get done…and we would have fun doing it.

Lighting for the Genesis camera is essentially lighting for film. There’s much the same dynamic range and latitude without the contrast issues that crop up in shooting HD. It has extremely high resolution so that in many cases the film out can appear “sharper” than an image captured on film negative. As to sensitivity, we started out rating the camera at ASA 500, but adjusted that a bit to ASA 400. Like film, the ASA is very subjective, and the way one cinematographer rates the material will differ from another. One delightful bonus of Genesis is that you can choose a virtual 360 degree shutter that doubles the sensitivity, enabling you to record the image in almost any light, no matter how dim. There’s a scene in Scary Movie 4 in which most of the exposure comes from the flame of a cigarette lighter.

In fact, when you’re lighting Genesis there are virtually no concessions that have to be made related to digital imaging. If anything, there’s an enhanced confidence level that encourages you to play a little closer to the edge. With that beautiful HD monitor in front of you, there’s no waiting for dailies. Even the focus pullers say they sleep much more soundly knowing that we catch any slight glitch right on the spot.

Although I don’t spend too much time in the “Tech Tent,” it’s a great refuge for final tweaks. Remember that with Genesis, we’re recording a Panalog file, and therefore, not doing any image grading on set. In fact, we have to apply a LUT (lookup table) to the monitor to at least give an approximation of what the picture will look like when it’s rendered on film.

Having said that Genesis doesn’t change the way we light, each movie brings its own challenges. On Balls of Fury, we had a lot of work scheduled in Christopher Walken’s “lair” including a large, low-ceiling dining room in a defunct Chinese restaurant. Our widest shots had a top frame line that was only about 18 inches below the ceiling. Hanging any lights at all, let alone the soft boxes or Chimera bags that I like, was not really possible. To compound the problem, we had several major scenes to shoot in there, and we needed to rig a system that was flexible and quick to adjust. Ultimately, I decided to make a huge array of “China balls,” a hundred of them, which were arranged in tightly-spaced rows above the dining room. Every lamp was on its own dimmer and could be joined with any of the others in an endless variety of patterns. With my gaffer, Alan Colbert, I could shape the light exactly to the needs of each shot. The China ball array worked great, and we’ll definitely be using it again in the future.

| Post Your Comments & Questions about this topic here >> |

SF: You said that Scary Movie 4 was the first project you shot with the Genesis. Could you share some of your thoughts in regards to this?

SF: You said that Scary Movie 4 was the first project you shot with the Genesis. Could you share some of your thoughts in regards to this?

Thomas Ackerman, ASC: HD had been Ben and Tom’s frame of reference on their TV show and just-completed feature, Reno 911!: Miami. They had heard glowing claims about Panavision’s Genesis, which I call “HD on steroids,” and were delighted to know that I had already shot Scary Movie 4 with the new system. In fact, that was the first production in release that had been shot with Genesis equipment.

My experience on SM4 was all good – after extensive testing in pre-production, it was apparent that Genesis really did approach the contrast of film. Also, it was robust and user-friendly. Shooting a movie is a huge undertaking. Nobody wants to be tweaking and messing with the camera when you ought to be making shots. Apart from recording the image digitally instead of on film, there was nothing different in our process on set. My lighting didn’t change, we moved the camera with the same freedom as a Panaflex; we worked long hours in horrible weather. Due to its Super 35-sized chip, Genesis also supports all the standard lenses – a huge advantage when compared to standard HD and its irritating back focus problem. With Genesis, the angle of view and depth of field are exactly the same as shooting 35mm.

One small drawback was the limitation in high-speed shooting. The Genesis currently tops out at 50 frames per second so that shooting slow motion often means bringing a film camera into play. This isn’t really a big deal since the Genesis output and film, in our case Kodak 5218, look exactly the same when you project them side by side.

Of course when you shoot Genesis, there’s a digital intermediate waiting for you down the road. This is a great resource, obviously, as it affords so much more control than a traditional photochemical finish. I think the trick is to exploit all the advantages of the DI suite without being seduced or literally buried in the possibilities, like a kid in the candy shop. For example, photographic decisions can be greatly influenced by all the fancy tools in post production. Maybe you’ll decide not to have the grips rig a teaser on a giant soft light. You might choose not to use a graduated filter on the camera. These are things that can be done later in DI grading and at less cost. However, there’s no magic bullet that will light the set beautifully, or frame a shot, or accomplish any other, other stuff that goes into photographing a motion picture. Digital intermediates still require that people of talent and vision create the images in the first place.

SF: Scary Movie 4 spoofed Saw, The Village, The Grudge, War of the Worlds, and other movies. Could you discuss some of these scenes in regards to lighting?

Thomas Ackerman, ASC: When I started thinking about the photography on Scary Movie 4, it was focused on the films we were going to spoof and what made each of them unique. The filmmakers were old hands at the genre, and they knew that any “target movie” had to be popular and well-defined in the audience’s mind. You can’t spoof films that nobody saw. All the films that were incorporated into SM4 also had a clear set of visual rules. From the dreary monotone of The Grudge to the maxed-out conceit of War of the Worlds, we had lots of stuff to mimic.

In some cases, we reproduced individual shots and scenes very carefully. For example, our production designer, Holger Gross, reconstructed the Grudge house down to the last little detail. The establishing shot of Anna Faris entering the house was framed exactly as it had been in the original movie. Anna’s wardrobe, the lighting, the color tone – all these elements put you immediately into a Grudge mode. There were a number of these “prove it” moments sprinkled throughout, which gave us license to do whatever we wanted with the rest of the coverage and visual design. As long as it was “Grudge-like” it didn’t have to be a slavish copy. In fact, the audience doesn’t laugh at the photography, they laugh at the jokes. You’re responsible for getting them to that point.

It’s really interesting to hear what people think they saw in a movie. One review said something like, “David Zucker has recreated War of the Worlds shot for shot, and for a fraction of what Spielberg spent.” Well, what we did was infinitely less than a carbon copy. Budget obviously was one reason. But there was a conceptual reality too. Ultimately, all the spoofed films, each with its own set of rules and unique qualities, had to be joined in a single story called Scary Movie 4. Craig Mazin, Jim Abrahams, and Pat Proft wrote a script that skillfully accomplished that, and the photography had to do the same thing. The audience had to go with all the different spoofs while watching a single movie – the one we were making.

In terms of War of the Worlds, the reviews proved something to me. Just a few strong shots can convey a huge impression. We really did our homework and worked hard to deliver the goods in the big night battle sequence. There were a lot of pyrotechnics, the orange rim light on the Humvees, all the tracers streaming…and of course, the SM4 version of the “tripods.” It was far from a shot-for-shot replication, but enough strokes were there to make the experience complete. It’s basically slight-of-hand.

SF: You were the Director of Photography for The Battle of Shaker Heights for Project Greenlight. Could you share some of your thoughts on this, and do you have anything to say about how the directors were portrayed on Greenlight ‘03?

Thomas Ackerman, ASC: When someone asks about my experience on The Battle of Shaker Heights, the underlying curiosity is about shooting for new directors. In this case, of course, Kyle and Efram were not “new” directors. They had a number of excellent short films to their credit, which were seen in part during the “contest” phase of Project Greenlight 2. Amazingly, there has been quite a bit of collective amnesia on this point. Some people I’ve met ask about these guys as if they were inexperienced amateurs who were simply given this opportunity on a silver platter. What about their prior films? You see a lot of solid work there in terms of concept and execution. Also, tenacity and discipline, without which, no independently financed short film can be brought to a successful end. So the truth is that Efram and Kyle were as prepared as many directors who are assigned, not “given,” their first feature film. Likewise, they fared as well, or much better, than some of their newbie counterparts. I always wonder how the geniuses who loved to put them down would have fared had the roles been reversed.

In any case, among the reasons I chose to do that project - I’m a sucker for enthusiasm as long as there’s talent and discipline backing it up. I also wanted to see if I could still shoot a movie in 22 days and be completely uncompromised in the effort. There was also a bit of hubris, I guess, in my total confidence that we could survive 2 months of reality show scrutiny. Misplaced as that confidence may have been, the end results were not embarrassing for the crew. Not that the PGL harpies weren’t ready to pounce. Our wireless mikes were constantly monitored, and at the slightest hint of a juicy “incident,” the video cameras were deployed.

This intense documentation, when combined with the editorial slant of Project Greenlight, led – not surprisingly – to portrayals of Mr. Rankin and Potelle that were often unflattering. But from my view, in all but a handful of cases, they conducted themselves effectively and honorably. Incidentally, the crew would emphatically agree. These two guys did their homework, understood their craft, and were imminently well-qualified to be directing their first feature film. Did they have all the answers? Was there an occasional blunder? Were they ever frozen in place by that fear that stalks virtually ALL first-time feature directors? …Otherwise known as, “My dream came true. Now what the hell do I do?”… Of course. And who would have expected anything different?

Any young filmmaker who gets their first movie has to know that they’re under the gun. Even if it’s money from Daddy, there’s a quid pro quo. You gotta take the pressure and somehow make the art. And if you agree to be the subject of a 12-episode TV show, know this too: your behind-the-scenes story may not be told as you would like it to be. I think Kyle and Efram were keenly aware of implications of all of this. They gave the devil his due and wisely never logged onto the web sites where they were routinely pilloried. They got to make their first feature film and are successfully on track with their careers.

SF: Is there anything that you specifically want from a director or don’t want from a director?

Thomas Ackerman, ASC: When I talk to a director about doing a particular project, there’s already been groundwork laid. In many cases, our agents have already been involved. Then the cinematographer needs to consider the screenplay very carefully. This reading may take place before casting, so the story has to communicate on its own. Then comes the all-important meeting in which the director lays out his or her expectations. I guess what I value the most is candor. It’s really helpful to have the unvarnished version. Passion is also a pretty strong draw. Making movies is a giant undertaking, so you kind of like to know the director absolutely loves the project. They’re looking at me the same way: can this guy make it to the end of a long day and still have good ideas? And just as important, will he still be civilized? A movie set even under the best conditions, can be a bit of a pressure cooker. It’s essential that directors and shooters agree on how to “keep the genie in the bottle.”

When a director hires a cinematographer, they’re going to be spending more time together than any married couple, at least for a few months. So the process has got to work. There has to be trust and a common vision. The best photography happens when there is this unbreakable link between the two people. Maybe the director has an awesome shot idea, or the DP has a phenomenal lighting concept… But at the end of the day, their efforts will wind up on the screen all mixed together. So finally it only matters that it’s great work.

SF: You’ve worked on numerous comedies, including recently: Scary Movie 4, The Benchwarmers, Are We There Yet?, Wake Up, Ron Burgundy: The Lost Movie, Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy... What do you like the most about working on comedies?

Thomas Ackerman, ASC: I’ve shot lots of comedies over the years, maybe more than my fair share. I think the volume is related to quality. If all these movies were just flat-lit talking heads, I doubt the genre would have kept me interested. But I’ve been fortunate enough to work on films that were funny and had high photographic aspirations as well, where there was a smart director and producer who had taste and judgment. Where there was superb production design and a visual concept that supported what I was trying to achieve.

This isn’t to say that we haven’t contributed to the archive of pratfalls and fart jokes. Of course, there are many worse things than making people laugh. Actually, that’s sort of weird – the way we commonly refer to “making” an audience laugh as if it were a form of coercion. In fact, people want to laugh. They need to laugh. It’s the filmmaker’s job to issue the invitation. Writing, directing, and acting comedy is an exacting process. Totally unforgiving. Obviously, not all comedy is cut from the same mold, but there are strict requirements. You ignore them at your own risk.

How do you shoot funny? Basically, I think that’s impossible. However, there are choices you can make to support the joke or, just as important, to avoid sabotaging it. Framing, for example. Obviously, in a sight gag, there are certain elements you want the audience to notice, and in a certain order. There’s also a question that constantly arises when we’re shooting a big stunt: how dangerous do you want it to look? There’s a fine line between funny and making the audience uncomfortable, or worse yet, taking them out of the movie. For example, Walter Matthau’s stunt double does an astonishing fall in Dennis the Menace. The guy looses his footing and falls flat on his back in a way that would sever anybody’s spinal column. You just don’t want to see a senior citizen, even a curmudgeon like Mr. Wilson, get that kind of punishment. Anyway, when we were lining up an extremely low 3/4 angle to “sell” the stunt, it just seemed wrong, too heavy-duty. Ultimately, I shot it in profile. Just a simple picture that told the story but didn’t try to be too serious. It was still an awesome feat. But we went from cringing to laughing with a six-foot change in camera position.

Getting back to whether photography makes a film funny, it really can’t do much on its own. Whether people laugh has everything to do with the script, the director, and the actors. The cinematographer doesn’t just glue on a look. Like any other film you have to get under the skin. The world we created for Beetle Juice was so different from Jumanji, even though both movies shared common ground. In each, there was a bizarre parallel universe which overlapped and finally enveloped the characters. These films also shared another quality that, if anything, typifies my approach to photographing comedies: You don’t short-change the look, the lighting, the texture. If it’s supposed to be dark in a cave, as in the memorable scene between James Coburn and Cuba Gooding in Snow Dogs, then it’s a tiny bonfire that’s going to motivate the light. It’s going to be dark and rich, which supports that moment in the story. In turn, that’s the thing that helps the audience to buy into this unlikely father and son. It’s what sets up the jokes that follow. It also gets people up on their feet and cheering in the big dog sled race. When the director is going for believable performances, I want the pictures to be a part of the process.

Of course, comedies are often larger than life, and the camera has to help. When Clark Griswold fired up the ultimate holiday light extravaganza in Christmas Vacation, we knew it had to be an unforgettable icon. The entire Griswold house had to be covered with lights, to a ridiculous extent. This near-nuclear event had to be bright enough to wake the whole neighborhood.

In the same vein, Brendan Fraser’s climactic vine swing in George of the Jungle had to be “the mother of all vine swings.” It was so fast that Brendan’s face was horribly deformed, just like Chuck Yeager riding a rocket sled in that famous newsreel from the 60’s.

SF: Going back to Balls of Fury, he didn’t act in the movie, but what was it like working with actor, writer, and director Ben Garant? Could you describe your working relationship with him?

Thomas Ackerman, ASC: It was great fun shooting for Ben Garant on Balls of Fury. As a seriously hyphenated guy – actor, writer, and director – he approaches the job on very solid ground. Also, the fact that Ben and his partner, Tom Lennon, co-produce Reno 911! gives him a sense of overall responsibility and the ability to resolve issues objectively. Ben has the best of two traits: strong ideas, which he will vigorously pursue, and yet he’s flexible. He’s comfortable with the process so that he can take an outside view, very well-informed as I said earlier by the experience as writer / producer. Ben was never reluctant to add a shot, do another take, or insist that we go the extra degree of perfection. But at the same time, he was happy to print the first take when he knew it was exactly perfect. Ben Garant is one of the most decisive people I’ve worked with. When it works, it works, and there’s no need to belabor it. This self-assured confidence level does a lot for the actors, and the crew, as well. You know there’s a steady hand at the helm.

SF: What were some other things you enjoyed the most about working on Balls of Fury?

Thomas Ackerman, ASC: Of course, we had a wonderful cast, too. Christopher Walken, Dan Fogler, George Lopez, Maggie Q, Jason Scott Lee, the venerable James Hong …what a list! And it goes on. Every single actor was totally into the project. You could tell by how hard and how enthusiastically they worked, and by the incredible patience they showed when the going was rough. Shooting sports and martial arts takes a tremendous amount of discipline. Then on top of all that there’s the comedy, which is also a precise art. Christopher and Dan had a big third-act showdown in which they play “ping pong to the death” while negotiating a really unsteady suspension bridge. Plus, they’re wearing heavy costumes. It all came off without a hitch. Ben made everyone aware of what was needed, we did two or three takes of each angle, and that was it. During pre-production, there were several meetings on that one sequence, which really paid off.

SF: I understand that your daughter worked as a camera department PA on Balls of Fury. Could you talk a little about this experience?

Thomas Ackerman, ASC: Another new experience on Balls of Fury was having one of my children on the crew. My daughter, Caitlin, was lucky enough to be hired as our camera department PA. Coming just before her sophomore year at NYU, it was a wonderful opportunity, and Caitie was completely thrilled to be involved. Although there was no question that she could handle the job, I did have a couple of moments before she filled out her start slip. You know, the typical dad stuff hoping it would go all right, because when you’re the DP’s kid, there’s no refuge from a mistake. Actually, I think the standards tend to be a little more stringent when there’s nepotism involved. I told Baird Steptoe, the key assistant, to forget Caitlin’s last name. She worked for him and beyond that… Well, you get the idea. No special treatment. Anyway, Caitlin did great work and made me extremely proud. Not just because of the hundreds of pounds of Genesis batteries she schlepped around everyday, but because she earned the respect of the crew. People skills are so important in this job. It’s pretty hard to fake it on a movie set.

| Post Your Comments & Questions about this topic here >> |

This article may not be reprinted in print or internet publications without express permission of StudentFilmmakers.com. The above photos may not be copied or reproduced.

Check out this article in the June 2006 print edition of StudentFilmmakers magazine, page 46 .

Click here to get a copy of the June 2006 Edition, so you can read and enjoy all of the excellent articles inside.

About StudentFilmmakers Magazine and StudentFilmmakers.com

Learn about the Latest, Cutting-Edge Technologies and Techniques at StudentFilmmakers.com and StudentFilmmakers Magazine, the #1 Educational Resource for Film and Video Makers covering various topics with special focus on: Development, Pre-Production, Production, Post Production, Distribution. Article categories include: Cinematography, Lighting, Directing, Camerawork, Editing, Audio, Animation, Special FX, Screenwriting, Producing, and more. Watch, upload, and share your films and videos in the video section at: networking.studentfilmmakers.com/videos. Network and connect with filmmakers around the globe using the Filmmakers Social Networking Site at: networking.studentfilmmakers.com. Share your ideas, post your questions, and find answers in the online interactive forums moderated by experts at: www.studentfilmmakers.com/bb. StudentFilmmakers.com (www.studentfilmmakers.com) also produces and hosts film, video, and screenwriting festivals and contests, as well as educational workshops and seminars. Get the magazine, read the e-newsletter, and participate in the online portal and resource with free tools for film and video makers of all levels around the globe. With the technology changes coming faster and faster, we are all students.

StudentFilmmakers magazine would like to hear from you!

Click here to share your comments and feedback about the magazine, monthly editions, your favorite articles, and your favorite topics.

We always welcome and appreciate your Reader Comments. View them here, and send yours to the editorial team today!