by Rustin Thompson

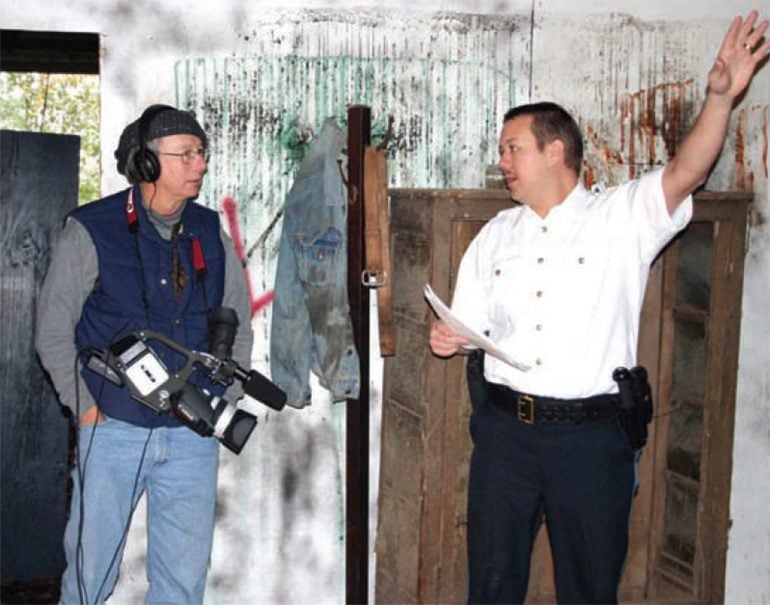

There is a kind of meditative awareness that takes over when I’m shooting close to my subjects, much like that of the skier or climber who focuses only on the physical elements right in front of them. The subject or character guides my eye, and my eye communicates with my hands, which then manage the camera’s iris, shutter speed, zoom, and audio level. I’m always dealing with matters of exposure and composition and focus, but also with how my subject is responding to my presence. I’m deeply aware of them as a human being, and truly grateful they’ve allowed me to be this close to them so I can bring their story to a viewer, to make a connection.

This is the “juice” of documentary filmmaking, this closeness to your fellow human, which dissolves borders of class, race, and language, at least temporarily. I don’t want to suggest this breaking down of barriers is permanent. You probably won’t become longtime friends with your subjects, nor will the divides of class and race magically melt away forever, but for the brief time of your shoot you will be communicating almost nonverbally. The experience can be profound. Getting close has become my way of looking at the world, my philosophy of visual thinking.

Before shooting my first independent documentary during the WTO protests, I was nonpolitical and disengaged with current events. I knew the basics of what was going on in the world, but I never went beyond the superficial, never investigated the nuances. But just one week in the streets, within a few feet of protesters and police, talking to them or capturing fly-on-the-wall sound, and then studying the issues in the evening, trying to catch up with what so many of these idealistic demonstrators already knew, changed me forever. Getting close to their passion ignited my curiosity. It taught me a new way of engaging with the world. It made me want to make films, both docs and short films for non-profit organizations.

Making these films introduces us to people who often come from different countries, circumstances, or lifestyles. They may be struggling with poverty or homelessness; they may be survivors of violence or learning to adjust to a change in their health; they may be targets of discrimination or exploitation. Often, they are activists and humanitarians rebelling against the label of victim, in turn forcing us to reevaluate our own privileges. Even after 20 years of doing this work, I am thankful for and honored by the opportunity to get close to their lives, if just for an hour or two.

Students and friends have asked me many times which I enjoy most, shooting or editing. I always think the answer will be editing, because that is where you turn raw material into stories, where the real creative process begins. But I think the two processes are linked. I’m energized by the characters I meet while shooting, by the reciprocal nature of our brief intimacy, by realizing that even though this situation is not new for me, it is quite possibly very new for them. This knowledge impels me to be alert and conscientious. The visuals acquire an innate energy, a role in the sequences I will construct later in editing. In that way, shooting and editing for me are inseparable.

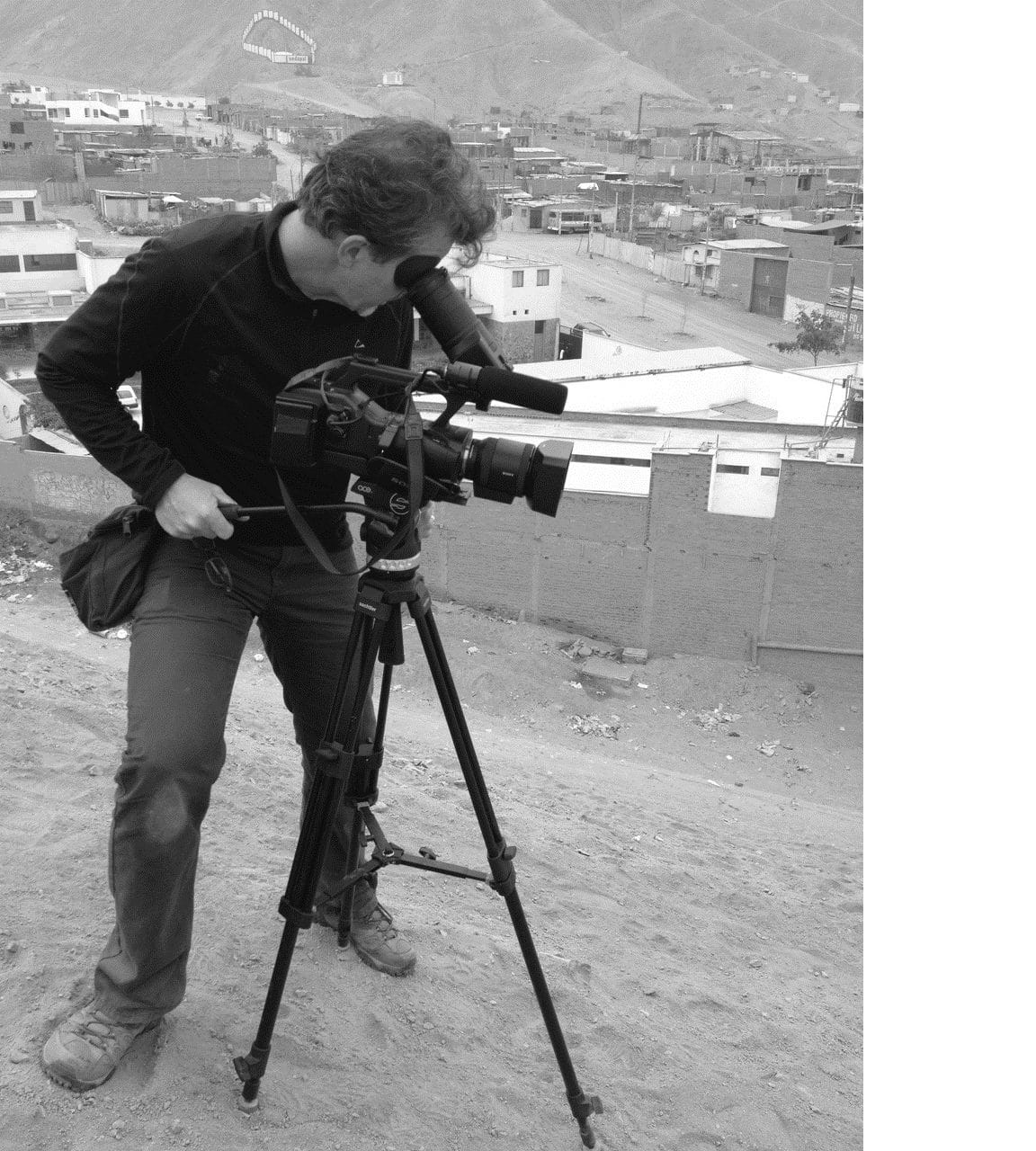

To get physically close, the first thing I do is get rid of obstacles in my way. I ditch the lights, the light stands, the flags, the reflectors, the slate, the boom microphone, the additional viewing monitor, the extension cords, the soundperson, the director (you are the director!), the unpaid intern, and, if I truly don’t need it, the tripod. I attach everything I need to the camera, or carry extra gear in a waistbelt or knapsack. This helps me to get intimate, dynamic footage, and greatly reduces the expenses and logistical hassles other crews or video-production studios often feel they need. I can work alone and still capture exciting images and quality sound.