STUNTS

Deputizing the Fight Coordinator Posse

Quick Tips on Greatest Hits

Written By Kevin Inouye

Hey, you, behind the camera or editing suite! Congratulations, you’re now part of the stunt team.

No, you won’t be set on fire, fall, or fight, but as with all departments, our work is only as good as what the audience sees…

Which means camera and editing have the power to ruin fight scenes…

Or not.

Lining Up Shots

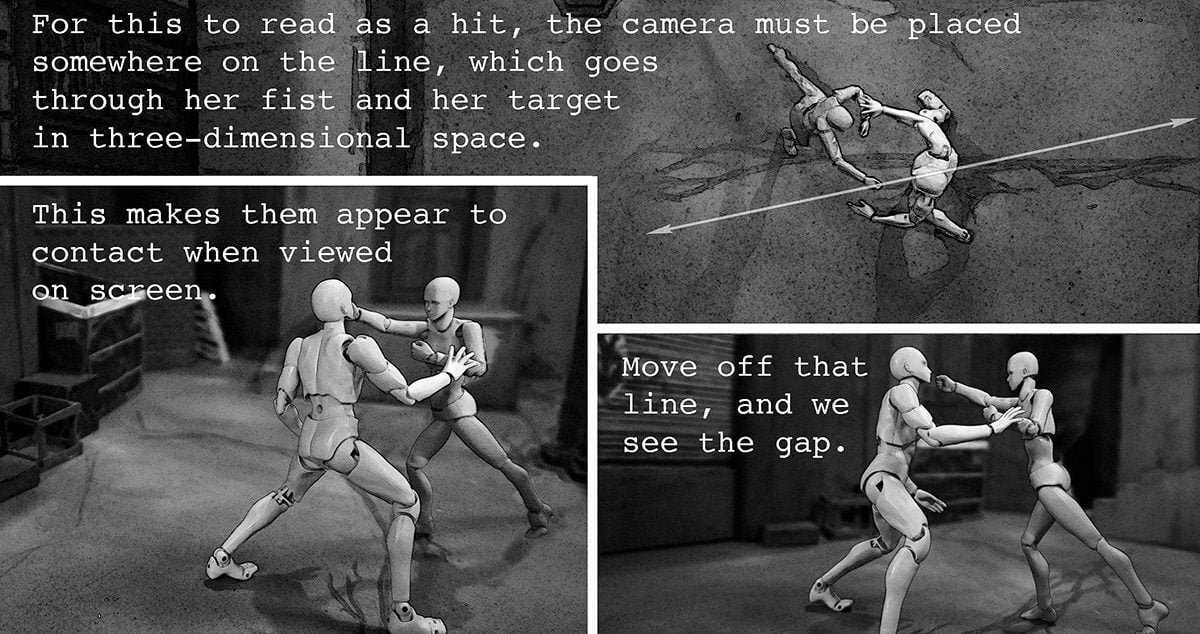

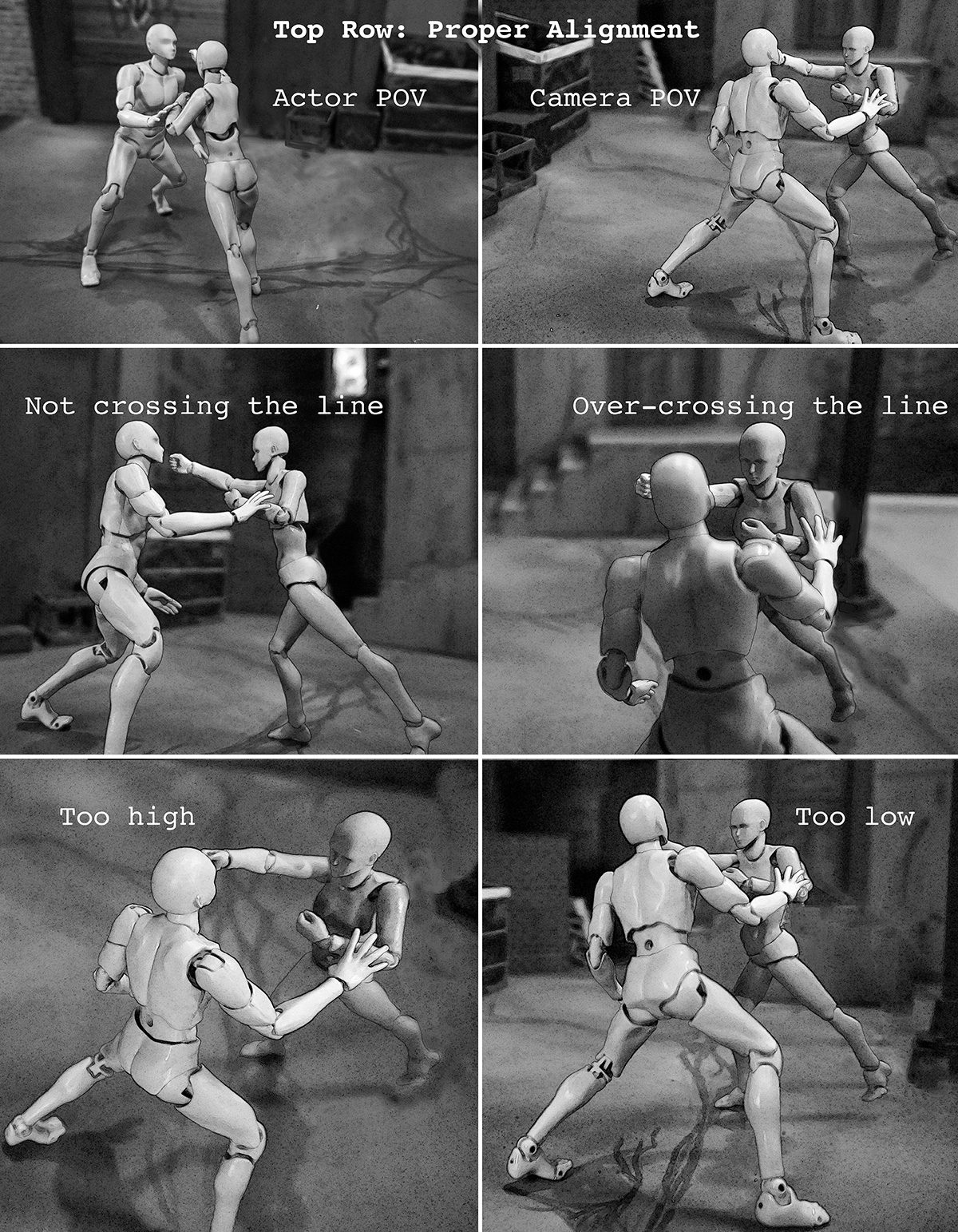

Most head hits, or strikes with non-padded props, are what we call “non-contact hits”. Weapon (fist, foot, etc.) and target never make contact, but need to appear to overlap on screen briefly. We want to see weapon traveling towards target, a moment of supposed impact, and then, an appropriate reaction.

When this illusion fails, it’s usually either angle or timing that’s off. Since timing reactions is also angle-specific, both have everything to do with camera location. Good stunt performers sell shots to camera almost every time, but elements like multi-cam setups, drone shots, or other complications mean your team needs to know what angle to sell each hit to, and the operator needs to hit those marks. Have half-speed camera rehearsals, and check how it’s looking. Often coordinators provide pre-viz, which can inform choice of shots, but if you want a different perspective than they rehearsed, you must inform stunt performers so they can adjust. It should go without saying, but directors, watch the monitor, not the set.

Ideally, coordinators watch a monitor and know when shots need to be redone, but student filmmakers or indie filmmakers running micro-budget sets may not have a video village, or people who know what to look for. There’s no way camera operators can focus simultaneously on framing, focus, light, acting, continuity, and when hits are selling, so have designated crew on monitor who know what they’re doing, or review footage before moving on to check specifically for whether hits sold. Editors, you may be sent takes with ‘misses’ in them. Please don’t use those bits!

These adjustments also apply to the illusion of near misses, blocked attacks, and offline elements (like a spear or gun aimed just to the side) still looking legitimate. Low angles and jib shots are cool, but they can also make it look like out-of-distance attacks are aimed way off target if performers don’t adjust. There’s no way to make the same non-contact attack look right both OTS and from a low angle without adjustment, so pick one per take.

Timing

Action places specific demands on rhythm and pacing. Humans have innate understanding of physics (we’d be injured frequently otherwise!) so playback speed can only be tweaked slightly before it becomes an obvious stylistic departure from reality… probably 10% at most. That said, selective dropping of frames right at or after the moment of impact can make hits look harder.

Cuts can be used to adjust timing, but these work best on matching motion, so overlapping shots is important. To cut mid-punch, shoot the whole punch at the end of one setup and again when beginning the next, so you can splice them almost like hidden cuts in whip-pans. This makes the 180 rule essential if you want audiences to be able to follow action!

Yes, you can cover for bad technique by cutting at the moment of impact, but audiences are savvy, and if you do that much, we’ll know it’s compensating for on-set failures.

Framing

Fights are high energy, so we want to fill the frame with motion. A punch traveling across the entire screen moves faster than the identical punch going halfway across it. That said, fights can move quickly and jerkily, so sometimes it’s expedient to shoot wider than you want, if you have sufficient resolution, and crop to frame the shot better in post.

On the other hand, we also want to be able to understand what’s happening with characters’ bodies, and medium or tight shots rob viewers of the chance to know what’s happening with stance or other body language. They hide some of the physical dialogue. Save closeups for inserts, when we need to see something like wounds, glances, weapons, etc. “Cowboy” shots, mid-thigh to top of head, are a great default. Of course, technical considerations also factor in, like needing to frame out mats, pre-applied wounds for a reveal, or avoid foregrounding rubber prop weapons that won’t look good in closeup.

There’s plenty more to consider in terms of sympathetic camera motion, visual energy, design, etc., but my point is that creating action is always a team effort, so those of you running camera or editing, don’t treat your job as just showing what the fight team did. Co-plan, co-create, and make everyone look better!

About the Author

Kevin Inouye is a SAG-AFTRA stunt performer, a fight coordinator, and armorer/gun wrangler through Fight Designer, LLC. He’s Assistant Professor of Movement, Acting, & Stage Combat at Case Western Reserve University, a Certified Teacher and Theatrical Firearms Instructor with the Society of American Fight Directors, a Certified Teacher with the National Michael Chekhov Association, and author of “The Theatrical Firearms Handbook.”

Visit Kevin’s websites at kevininouye.com and at fightdesigner.com.

2 thoughts on “Deputizing the Fight Coordinator Posse”

I realized that I never actually knew this until reading the article

If you watch something like this classic, 90% of the problems come down to the stunt performers having no clue where all the cameras on the soundstage were, or which take would be used, and the editors not knowing how to edit action: https://youtu.be/J0mUVY9fLlw