By David Appleby

Audiences are generally more tolerant of poor images than of poor sound. Students working on location often have problems with the audio but don’t take the time to improve it in post. If you read the credits of a feature film, you’ll notice the number of people involved in creating the soundtrack after principal photography has been completed. These include foley artists and editors, dialog editors, sound effects editors, and what I’ll be addressing here, the ADR mixer.

What is ADR?

ADR stands for Automated Dialogue Replacement, although it is far from automated. After the picture has been cut and for whatever reason dialogue recorded during production must be replaced, actors, engineers and a director (oftentimes not the film’s director) come together in a sound studio to re-record the dialogue that was captured on set.

In the old analog/film days, this was called, looping, because the scene on film was spliced into a loop so it could be projected repeatedly on screen as the actor tried to precisely match their lines.

When is ADR Required?

- To eliminate unwanted background noise.

- To eliminate mic noise such as wind or clothing rustle.

- To improve low level or unintelligible dialogue.

- To improve a performance.

- To add lines not originally in the script.

- To replace words not suitable for a network television broadcast.

- To replace an actor’s voice altogether, using a different actor.

Set-Up

- Place 1K beeps in front of each cue for playback. These are traditionally 3 beeps, and the cue starts on an imaginary fourth beep.

- Number each clip that you’ll be replacing for identification purposes.

- Set up mic(s). This is often a lav and a boom, or two booms at different distances, recorded on separate tracks with no EQ or compression.

The Session

- Watch the entire scene to give the actor context.

- Let the actor view and listen to a cue as many times as they need to get comfortable with the inflections and rhythm of the original performance.

- When they’re ready, mute the production audio. (There are times, however, that the actor will want the original audio left on their headset.)

- Announce the cue and take number for the editor and record the first take.

- Repeat until the actor and director are satisfied.

- Repeat all steps until all cues are complete.

What You’ll Need

- Multi-track recording software, allowing you to play back one track while recording on another. This makes things easier, but playback on one device and recording on a second can work as well.

- An assortment of lav and boom mics can help you to match the production audio while maintaining clarity.

- A high-quality speaker monitor system.

- Screens for the actor, director and engineer to view.

Guerilla Style

With the equipment available to you, you can do a good job by using a quiet laptop computer in a quiet environment, the same mic you used in production and two pairs of headphones. You sit in the same room with the actor, and they simply look over your shoulder at the visuals.

Cleaning Up

After cutting in the new audio, you can cut and paste words, syllables, and pauses – a frame here, a few frames there – to further tighten up lip sync. Room tone, recorded during production, will provide a sense of place and mask the gaps.

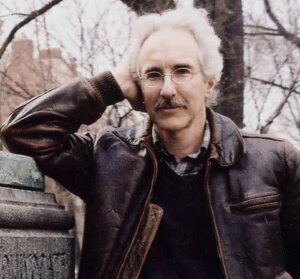

David Appleby is an award-winning filmmaker and professor emeritus at the University of Memphis. His films have aired nationally on PBS, ABC, A&E and Starz.