In the micro-budget world, we’re always endeavoring to craft a more cinematic look for our films. We’ll crop the footage to a wider aspect ratio, go for lenses and sensors that offer shallower depth of field, add fake optical flares in post-production… and yet, we still feel like we’re lacking that certain je ne sais quoi.

One of the main reasons? Anamorphic lenses.

These specialty lenses are often out of reach of even moderately-budgeted films, but so much of our time as cinematographers and indie filmmakers can be spent trying to emulate the look of them. So, what’s so special about them?

Originally, anamorphic lenses were crafted, alongside such developments as Cinemascope and 3D, as a means to combat the rise of television through achieving wider aspect ratios on 35mm film without sacrificing resolution. Originally, films were typically shot in the Academy ratio (1.37:1), and if you wanted to get a widescreen aspect ratio, you would have to crop out the footage at the top and bottom. Anamorphic lenses solved this problem by essentially squeezing the footage horizontally using a cylindrical front lens element and an ovular back element, so a wider image could still fit entirely into the boxy 35mm gate. Then the film was projected back out through a similar anamorphic lens to stretch it back out for viewing in a theater.

Still with us? Good.

Nowadays, because of 4K, the ease of cropping images digitally, and because most digital sensors are natively 16:9, anamorphic lenses are less necessary in terms of maintaining image quality. Instead, we crave them because of their LOOK: those streaking horizontal flares (made famous by the cinematography in the films of JJ Abrams and Zack Snyder), the ovular bokeh, the distortions and softness on faces and in the fringes of the image, and so on. Put simply, it feels epic, and expensive, in a way standard spherical lenses simply can’t duplicate.

As cameras and lenses have gotten significantly cheaper, we’ve been waiting for anamorphic lenses to follow suit, but aside from SLR Magic’s three-set of anamorphic prime lenses (which will still set you back a cool $8,500, they’re hard to come by easily. Still, if your budget allows for it, it’s important to discuss some considerations for what cinematographers should expect when working with anamorphic lenses for the first time.

For reference, I’ve included comparison stills from simple tests we did for Geoffrey Smeltzer’s short film titled MTA: Mass Teleportation Authority, using the Zeiss Compact Primes and the SLR Magic Anamorphic lenses on a Canon C300 Mark II, and color graded with Davinci Resolve.

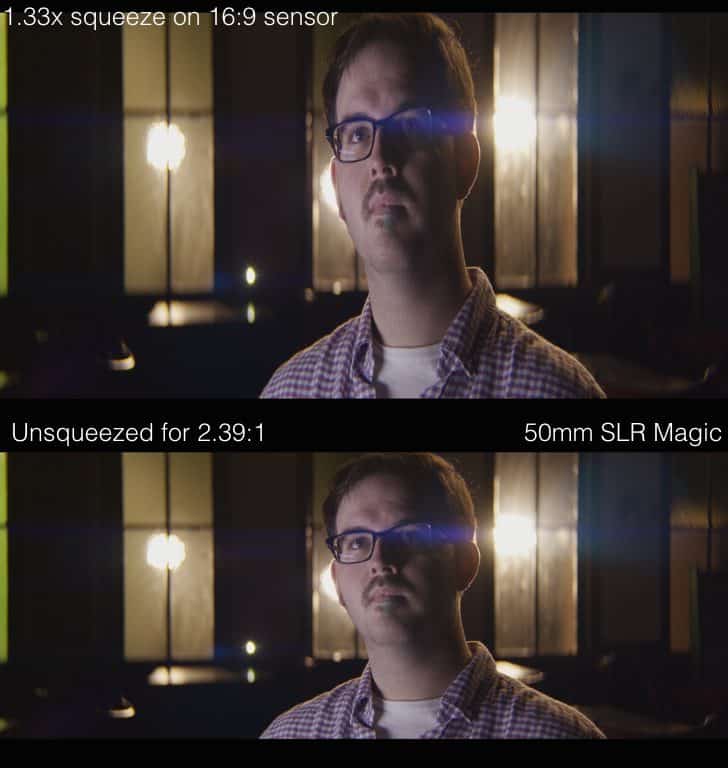

First, what camera or film format are you using? There’s an aspect ratio difference between the 16×9 sensor of a Canon C300 and the 4×3 sensor of an Arri Alexa or a Panasonic GH5, and that affects what anamorphic lens you should use. On a 16×9 sensor, you’ll want to use 1.33x anamorphic lenses to get that 2.39:1 footage, and on a 4×3 sensor, 2x lenses are your jam. (This means that the lens will squeeze the image either by a factor of 1.33 times, as seen in the stills, or even double it.)

However, this will also affect the way you think about focal lengths. We’re used to a 50mm lens as a pretty solid portrait lens, but a 50mm 2x anamorphic lens will actually resemble a 25mm spherical lens, as you can see from the comparison. Anamorphic lenses, due to the squeeze, are much wider overall; part of the reason they became popular was their ability to capture sweeping vistas in full on an otherwise boxy film format.

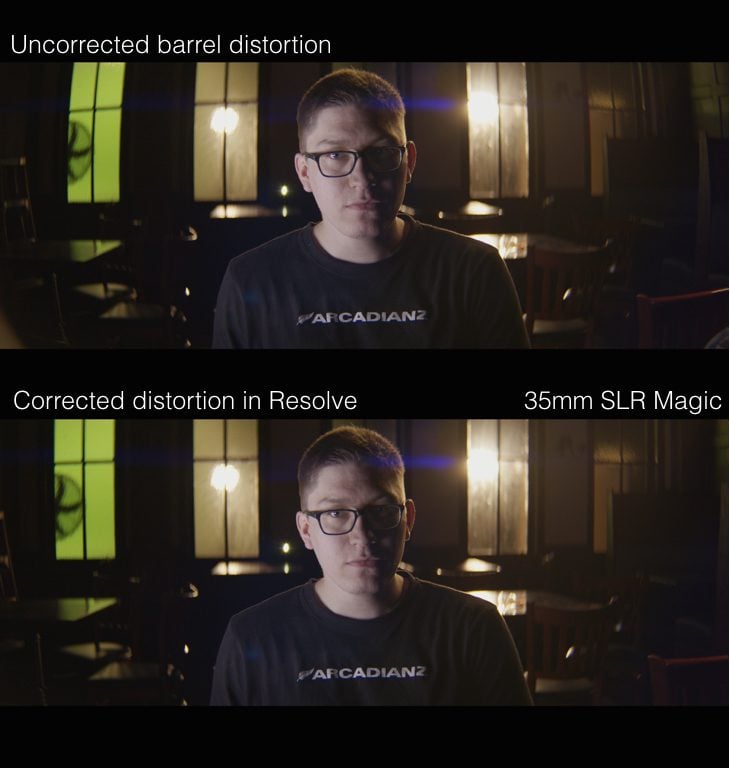

This contributes to the thing we all know and love about anamorphic lenses: distortion. That softness on faces, that hyper-shallow depth of field, that fringing and vignetting around the edges, those wild flares… they’re all part of the unique look, but some will have it more than others, and for some filmmakers going in expecting a cleaner look, you may be surprised that shooting wide open in 4K on an anamorphic lens results in a nearly unusable image due to the extreme distortion. Killing Them Softly features a prime example of this in a shot of Brad Pitt walking by a series of cascading fireworks. It’s an amazing shot that also illustrates what can be expected of these lenses, for better or worse. Luckily, several programs including Davinci Resolve have distortion correction that is pretty stellar.

Focusing with anamorphic lenses presents two issues: the lenses usually breathe when pulling focus (A Quiet Place offers several examples of this in the opening sequence), and it’s very hard to get close focus on a subject. Most anamorphic lenses can’t focus closer than a few feet, meaning lens choice for close-ups becomes paramount.

Lighting needs are probably the second biggest killer for low-budget films striving for anamorphic. Whereas some spherical lenses can open up to an f/1.3 or even lower, anamorphic lenses typically only open up to an f/2.8 and may not be sharp enough until you’re at an f/4 or even f/5.6. That means you’ll either have to boost your ISO to a noisier place, or up your lighting firepower and budget considerably. (For record, these anamorphic stills were all shot at an f/5.6.)

At the end of the day, you get what you pay for with these lenses, both in terms of optical quality and logistics. SLR Magic anamorphic lenses are accessible and give you those flares and bokeh, but their excessive breathing, distortion, and construction can make them challenging to use in the field. Because that lens gear is also on the front of the lens, using any sort of matte box isn’t really possible either, so internal or screw-on filtration is a must. You may find more expensive lenses to have a friendlier disposition.

So, as always, is it worth it? The creative and budgetary choice lies with you. I’ve found myself trying to emulate the look of anamorphics on spherical lenses, especially those flares, to no avail. Sometimes, you just need to bite the golden bullet.