Reference: StudentFilmmakers Magazine, May 2007. Solutions for Re-shooting a Film that Couldn’t Be Fixed in Post: Stretching Creativity Past the Limits by Myrl A. Schreibman. Pages 28 – 30.

Directing an industrial film is difficult enough. But directing an industrial film when you are brought in to fix something that someone else has directed is almost impossible. And fixing a badly directed project that cannot be fixed in editing and one that is a narrative story which must also instruct is close to ridiculous. But that was the challenge I was faced with.

The United States Department of Defense commissioned the writing of a short dramatic script based on the possibility of a third world terrorist hijacking a C-141 military transport aircraft with the U.S. Military resolving the conflict without any injury to U.S. service personnel. They assigned its production to a civilian/military film unit based at the now closed Norton Air Force Base in San Bernardino California and employed a director. When the fine cut of his movie was shown to the military producers, the picture did not work: it lacked the drama, scope, coverage and actor performance that was needed to tell a story. The hijacking of the aircraft while it was in flight did not make any sense, and the rescue of the pilot and crew by ground snipers had no suspense or excitement even though it was shot at night. Also, the capture of one of the hijackers wasn’t shot. No form of editing could fix those problems. They threw the problem to me to see if the project, with minimal re-shooting, could be salvaged. After discussions with Tom Denove my cinematographer, we decided to try. But they threw us a new problem! Very little money was left in the budget. Only enough for one night of shooting, and certainly not enough money to get the C-141 in the air to re-shoot the hijacking where the character relationships were developed.

Creativity works best when there are limitations and restrictions. And this project was stretching it to its limits. Whenever chaos sets in, directors must go back to the basics: story and character to find the solution to any and all problems. And that is exactly what we did. We had to go to the moment of the aircraft being hijacked in the air, (old footage), rework the story to allow for it to land, and while holding the crew hostage, it was to be refueled. When landed we developed the character relationships (new footage) before the rescue took place.

Tom and I did not know what a C-141 transport aircraft looked like so we were hustled over to the base tarmac to be introduced to our main character. When we saw it, we knew we were in trouble. A C-141 aircraft has a height of 39 feet, a length of 168 feet, and a wingspan of 160 feet. This was a big mother! The cockpit door to the aircraft is forward and about 25 feet above the ground, and the back end of the aircraft lowers and becomes a ramp permitting equipment, vehicles and troupe personnel to be loaded for transport. A C-141 is so large that it can hold two whales in their own tanks and still have room for a helicopter. (In Milos Foreman’s HAIR, the character Claude, with a battalion of soldiers, marches into the back end of a C-141 aircraft.) We were shooting in 16mm film, had no money to speak of, a small crew, limited lighting equipment, one night to shoot our fixes and a mega-giant player that was important to the story. And on top of it all, the mega-giant player, the airplane, had to be towed to the middle of the runway to shoot the sequence. How was I going to stage the scene? Or more importantly, how was I going to stage the master shot when the hijackers come out of the cockpit door, move them down the stairs that were moved in position by ground crew while holding the pilot and co-pilot hostage and then having them attempt an escape? We could do it easily without seeing the massiveness of the C-141, by showing the staircase and the front of the plane.

But that would not give the project production value nor engage the military audience into the reality of the size of a transport aircraft which was its reason for hijacking… (Besides, I knew that would be a coverage shot anyway!) We needed to somehow get above the aircraft on a wide shot shooting down the plane’s fuselage and follow the hijacker down the stairs to the tarmac. The change in perspective in one shot would show the audience the power and strength of the aircraft and its potential importance for hijacking while at the same time bring us into the drama of the characters in conflict in the story. I intended on playing the scene that focused on character relationships at the bottom of the stairs before the hijackers tried to escape. This would let us easily move in for tighter shots like the close-ups and extreme close-ups that the story needed.

We needed a crane! And a crane that can go above a four story building (39 feet) and then could come down to move in closer to our characters and the story elements. But there was no money in our budget to rent a crane.

Tom was using a couple of platform scaffoldings from Norton Air Force Base for his lights to light the aircraft and the scene, so we knew we had the possibility of a high angle shot if we could get one more scaffold from the Base. But I needed the shot to move motivated by the actors coming down the stairs. The fixed scaffold was not the answer. As Tom and I were scouting the location, we noticed that the airmen were cleaning a C-130 aircraft using a “cherry picker” from which they washed the top of the aircraft. We noticed that the lift element of the cherry picker was not extended fully and wondered how high it would be if it were? We asked. It went up to 45 feet. We had found our solution. If we added a tripod or a six foot camera operator on the cherry picker, we could get the camera 51 feet in the air; high enough to find our angle over the C-141 at the top of the shot. Now the problem was to find a way to move the cherry picker with the action. We continued to watch the C-130 bath and noticed that when operated, the cherry picker had a jerky movement going up and a smooth movement coming down, when a light bulb went off at the same time in both mine and Tom’s heads. He turned to me, and we said simultaneously to each other, “Let’s get this cherry picker for our shoot.”

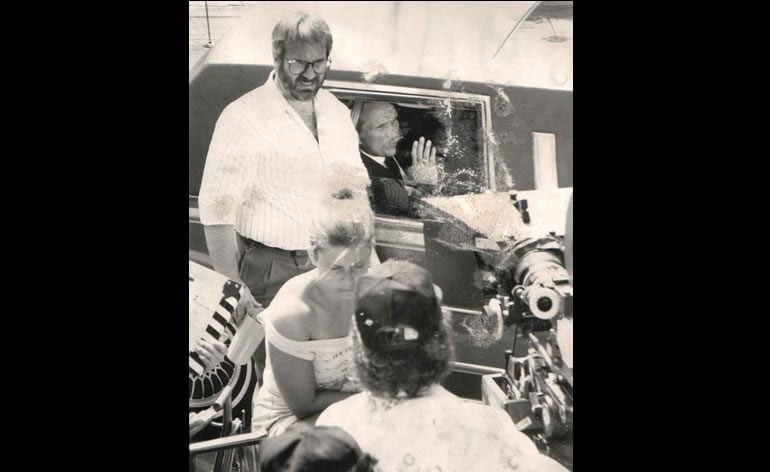

The night of the shoot, we positioned the cherry picker about fifty yards away from the aircraft towards the front of the fuselage. I dramatically staged the actors to come out of the plane and move down the stairs to under the wing with one of the hijackers holding a prop pistol at the head of the actor playing the pilot. Real military snipers portraying actors who were snipers were positioned for the camera shot. Tom and I went up in the cherry picker to set the head of the shot and see what we could do for the descending camera movement from the cherry picker.

Every time we tried the shot we just couldn’t make it look right. It kept looking like we were just doing a high angle shot that was descending straight down. If we added a zoom movement to the image, it became too mechanical, unrealistic and very cheesy. It did not provide any drama to the movement that the shot needed. Finally, Tom told me to get off the cherry picker and just leave himself and his AC to do the shot as he had an idea. I was fine with this since being 45 feet in the air on a small platform was not my idea of a good time. He asked me to call a rehearsal again, and we raised the cherry picker to the top of the shot. Only this time, Tom was positioned by the back corner of the cherry picker platform hand holding the camera, and when I called action, and the cherry picker began to descend, he moved to its diagonal front corner. After the rehearsal, he motioned to me a ‘thumbs up’ to shoot it.

Knowing that we were limited in time with this night shoot, I trusted his dramatic storytelling skills and called for “picture”. The camera rolled. We had camera speed. I said “action”. The actors fully in character and snipers at the ready executed their staging perfectly, and the cherry picker made its move while Tom made his. Then in a brief glance I noticed that the AC was adjusting the zoom as Tom made his diagonal movement and the cherry picker descended. Brilliant! When we saw the dailies, we saw what we now label as a “poor man’s” crane shot. The slight dolly movement while zooming in to a tighter shot while the cherry picker was descending changed the axis of the shot just enough to provide the dramatic element we needed for the master without drawing attention to the zoom. And the shot gave us the direction the coverage of the scene needed to take.

When we finally finished the sequence which included snipers firing and one hijacker getting hit and another running away from the scene, we discovered we had about two hours of darkness left. Not enough time for a small crew to strike the lights being used with the C-141 and move them nearby to light an area we were using for the capture of the fleeing hijacker. I turned to Tom and asked, “What do we do?” Tom told me and the gaffer to drive our cars to the next location nearby and he would drive his. He asked me not to worry and for me to get over there first to stage the scene for him to look at once he got there. Rushing over to the next location I hoped the sun would delay its rise just a few more minutes. When Tom arrived I showed him the basic staging of the actors. We briefly discussed how to shoot the master focusing on the story noting how much time we had before the sun would rise. Thinking he brought some lights with him he then asked for the keys to my car. The next thing I knew he positioned the headlights of our two cars as back lights for the scene, and had the gaffer’s car headlights as the cross fill for the actors and the location. After shooting the master I created selective coverage always working the staging for the headlights of the three cars. We shot the entire scene using only car headlights and finished it just as the dawn was breaking in the eastern sky. Necessity is the mother of invention and creativity is its father!

Myrl A. Schreibman is a Producer/Director, professor at UCLA Film School, and author of the book, “The Film Director Prepares, A Practical Guide for Directing Film and Television.”