HOW-TO, Techniques, & Best Practices Channel

| Notes on Camera Movement: When to Move the Camera and Why By Staff posted Jan 26, 2010, 08:11 |

Check out this article in the print edition of StudentFilmmakers

Magazine, March 2007. More photos featured in the print edition. Click

here to get a copy and to subscribe >>

Notes

on Camera Movement

Notes

on Camera Movement

When to Move the Camera and Why

by M. David Mullen, ASC

| Page 1 | 2 |

Motivation is not just something actors need � it�s something cinematographers

and other cinema artists deal with every day when making a movie. This not only

applies to how a set is lit, but also to elements like camera movement. When

to move the camera, why to move the camera, ultimately matters more than how

you move the camera.

As a cinematographer, I have to incorporate the tastes of the particular director

I�m working for when designing how a sequence will be shot. Some like to find

as many opportunities as possible to move the camera; others would prefer to

only move the camera at very key, specific moments. My own personal taste is

somewhere in between. I dislike unmotivated, excessive movement, yet many of

my favorite moments in cinematic history involve some sort of camera move, from

the fast telephoto panning in Kurosawa�s movies to the endless traveling shots

in Kubrick�s films.

There is a basic truth that camera movement tends to weaken composition and

lighting, yet what it can add is energy, often justifying the loss of control

over the first two elements. Of course, there are moments when an inappropriate

movement can deflate a shot�s visual tension and become a distraction to the

screen action.

Often on independent feature productions, there is an attempt to find ways of

moving the camera because it is generally felt that camera moves � particularly

slick ones on Steadicam, dollies, or cranes � add production value. This is

an understandable desire to want to make one�s movie look bigger-budgeted than

it really is. However, it doesn�t get around the fact that the movement must

be there for some dramatic or logical reason; also, the movement shouldn�t cause

a loss of production value by making the elements in the frame less controllable.

I�ll relate some personal experiences dealing with moving the camera. I photographed

two small studio features recently, Akeelah and the Bee (Lionsgate) and The

Astronaut Farmer (Warner Bros.) Though the second one had twice the budget of

the first, the first had twice as much camera movement.

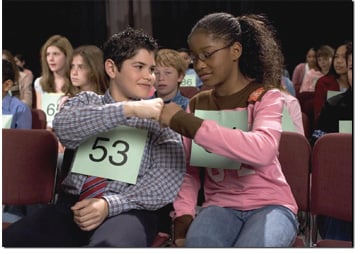

On Akeelah and the Bee, the subject matter revolved around spelling bees. Doug

Atchison, the director, had assured the studio he would make spelling bees look

exciting by shooting them as if they were sporting events. In theory, this was

a sound idea, but in practice, it was quite a challenge. The truth is the fast

camera movements and editing during a sporting event is naturally motivated

by the fast action going on in front of the cameras. In our case, we had someone

standing still in front of a microphone spelling a word.

To crank up the tension and energy of these events, we tried every trick in

the book on our limited budget and schedule: crane shots, fast dolly ins and

outs, 360 degree dolly moves with zooming as well, whip pans, Steadicam moves,

snap zooms, etc. All centered on this person standing still at a microphone.

Therefore the movement wasn�t naturally motivated, but it was emotionally motivated

to underscore the pressure these contestants were under. But it was a very risky

approach in that it could become a bit like the forced humor that comes through

the use of �funny� wide-angle lenses on close-ups. The energetic style probably

worked the best when we were doing montage sequences because it created a musical

quality that was well-suited for editing to music.

Because we were on a tight schedule, we storyboarded these spelling scenes very

carefully so as to shoot only what we needed to make the editing work. Luckily,

I could do much of the coverage under the stage lighting used for these events,

allowing me on some days to do as many as 75 set-ups in under 12 hours of shooting.

Our work was complicated by the fact that our lead actress, who is in 90% of

the movie, was a minor, and the child labor laws are strictly enforced by set

teachers here in Los Angeles. There was no such thing as �grace� when it came

to needing the actress for a second take if her time was up, so there are a

number of ambitious shots in the movie which were the first (and only) take.

The most memorable was probably the biggest shot in the movie. We had to establish

the audience and TV cameras that faced Akeelah at the National Spelling Bee.

The shot started on her eyes, zoomed out to a close-up, and then dollied 360

degrees around her as it zoomed out to show the 1000 audience extras plus 200

kids on stage behind her. When we got around to this shot, I was informed that

our actress had to be gone for the day within fifteen minutes. Luckily, most

of the stage and audience area (at the Hollywood Palladium) had been pre-lit

to some extent, but we had to quickly build a camera platform that extended

from the stage in order to place the circular track that surrounded the Akeelah

standing at the microphone on the edge of the stage. The grips got that built

in ten minutes, the lighting was finished, we put the camera up, and I zoomed

in and got a quick eye focus, and then we shot the rehearsal, with all 1200

extras in the shot. And I believe that�s the shot in the movie, in the trailer,

etc.

But the purpose of the shot was not just to be fancy. We had to establish first

her apprehension by being tight on her eyes, then establish what she was up

against by showing the crowds surrounding her, and then end back on her face.

The Astronaut Farmer was made with a very different aesthetic approach. Set

on a ranch in Texas (though shot in New Mexico) it has an Americana feeling

of the Old West meets the Space Race. Our visual inspirations were Norman Rockwell

paintings, western landscape paintings, and 1950�s NASA steel and chrome futurism.

Our framing and lighting was designed to look �painterly,� and camera movements

were designed to not interfere with that look. Therefore, the moves were very

elegiac and lyrical when they occurred � slow, graceful, sometimes with a slight

rise or fall. It was the minimalist aesthetic of a John Ford film.

One common mistake directors make when designing a camera move is beginning

the scene on some unimportant but lyrical object, slowing moving past it and

through the space, and finally landing on the beginning of the dramatic scene

itself. The trouble with this sort of opening to a scene is the moment the movie

runs long in the first cut, a shot like this will be the first thing to be eliminated.

The editor will �cut to the chase� as they say. You want to design moving shots

that are intrinsic to the scene and will probably not be deleted later. For

example, a slow push-in on an actor�s face as they deliver the key piece of

dialogue will probably survive any edit of the movie. Movements that follow

important action or follow an actor as they cross the room and deliver important

lines � these are likely to remain in the final cut. This is all to say that

designing a sequence with camera movement to some extent requires that you think

about how the scene will be edited.

| Page 1 | 2 |